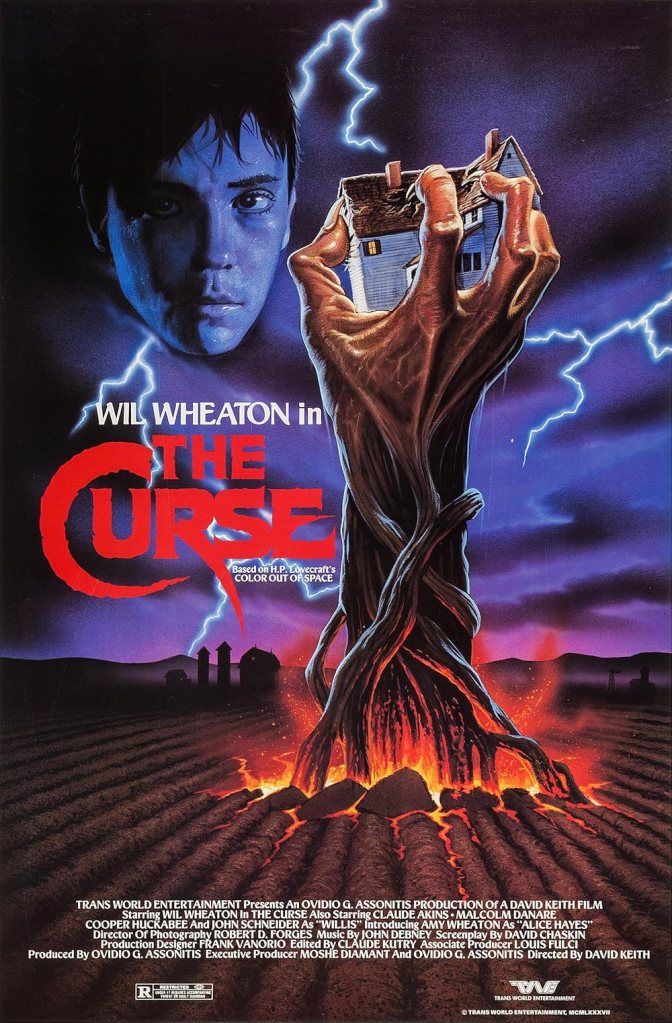

Matty takes a look at a squelchy Lovecraft adap and tracks its problematic making.

A couple of years before their takeover of Empire Pictures, Trans World Entertainment cashed-in on Empire’s success with Re-Animator (1985) and From Beyond (1986) by mounting an H.P. Lovecraft adaptation of their own. Using The Color Out of Space as its basis — the same tale AIP utilised for Die, Monster, Die! (1965) — and originally titled ‘The Farm’, THE CURSE (1987) stands as one of two films actor David Keith helmed for the company. Marking his directorial debut, Keith followed The Curse with the thoroughly lousy vanity vehicle — sorry, ‘action comedy’ — The Further Adventures of Tennessee Buck (1988). Trans World boss Moshe Diamant had initially approached Keith to merely star in Tennessee Buck and another project, the ultimately unmade thriller ‘Blood Hunt’. When Keith voiced his interest in directing them, Diamant conceded on the proviso he tackle The Curse first.

According to The Curse’s lead, Wil Wheaton, Keith was coked to the gills during filming.

The innuendos deployed by Fangoria during their set visit suggest the same.

“Keith is the dominant force of [The Curse],” the genre bible reported, an eyebrow raised. “He walks around the location, charged with energy.” Co-star Claude Akins complimented his “enthusiasm and exuberance”, and Keith himself was quoted as saying he was “so fired up!” all of the time [1].

Cocaine certainly explains Keith’s creative choices.

At the risk of spreading aspersions, there is a, erm, ‘snowy swagger’ to the film. A loud, brash arrogance and pseudo-confidence typified by overplayed scenes; an emphasis on gimmicky visuals; and a genuine belief that it’s probing big social, philosophical and theological topics. Of course, like anyone powered by Peruvian party powder, The Curse is nowhere near as suave or as profound as it thinks it is. Really, the film’s just a sweaty mess, ranting and raving at you in the middle of some random’s kitchen at five in the morning — but if you’re OK with that, there’s fun to be had.

Despite their explicitly garish presentation, several images pack a wallop and exude a pleasingly strange and nightmarish ambiance accentuated by Franco Micalizzi’s stirring synth-hick score. The icky practical FX — orchestrated by a fleet of Italian splatter veterans operating under an assortment of Americanised pseudonyms, their combined credits including slinging rubber n’ grue for Argento, Lenzi, and The Curse’s co-producer/second unit director, Lucio Fulci — sport a delightfully squishy tactility. And the story’s central themes — that of control and reality being stripped away by forces far beyond conventional human understanding — are as faithful to Lovecraft as they are to scripter David Chaskin, who’d tread similar terrain in A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge (1985) and across his subsequent Trans World production, the wonderful I, Madman (1989).

Best, though, is that The Curse is never, ever boring.

Partly shot on Keith’s farmhouse property in Tellico Plains, Tennessee and partly shot on soundstages in Rome (where, if behind the scenes murmurs are to be believed, Fulci – billed as ‘Louis’ on the credits – took a more hands-on approach at the behest of the film’s equally legendary co-producer, Egyptian B-movie maestro Ovidio G. Assonitis), The Curse’s plot finds Wheaton’s browbeaten teen watching his family turn into zombie goo when a meteorite crashes on their farmland and exerts a corruptive, body-bending influence. Keith said the film was less a horror, more a dramatic and provocative commentary on the terrible state of farming in the age of Reaganomics. Such a patently ridiculous proclamation does little to sway rumours of his colossal beak intake.

“I’m not a fan of horror films per se,” Keith told the New York Daily News, presumably between bumps. “I’m just a fan of good films… H.P. Lovecraft was one of the first great science fiction storytellers. Our script doesn’t follow his story completely, but it was based on it. We worked out conflicts that weren’t there, and we changed the location from Maine to Tennessee.” [2]

Lensed in autumn 1986, The Curse premiered at The Tennessee Theater in Keith’s hometown of Knoxville on 9th September 1987 and began its U.S. theatrical roll-out two days later, when it opened in California, Arizona, Ohio, New Jersey, and New York. While poorly received by critics, the film did well enough at the box office and on tape to warrant Trans World and their successor company, Epic, turning it into a franchise by retitling three otherwise completely unconnected productions/acquisitions of theirs. Assonitis’ stunningly barmy snake shocker ‘The Bite’ became Curse II: The Bite (1989); South African creeper ‘Panga’ became Curse III: Blood Sacrifice (1991); and ace Charles Band hair-raiser Catacombs (1988) became ‘Curse IV: The Ultimate Sacrifice’ when it finally graced North American video store shelves, a solid five years post Trans World/Epic’s aforementioned commandeering of Empire. Funnily, in the U.K., Catacombs actually landed on cassette – as Catacombs – ahead of The Curse. Catacombs arrived in late ‘88, The Curse spring ‘89. Both were issued by longtime Trans World and, indeed, Empire peddler Entertainment in Video who also unleashed Curse II as the moniker-less ‘The Bite’ in summer 1990. Curse III hit British shores two years later, when RCA/Columbia released it as ‘Witchcraft’ — which no doubt caused a great degree of confusion for fans of the identically named Witchcraft (1988) saga… [3]

Alas, beyond the film’s (likely) drug-fuelled delirium and the producers’ milking of its surprisingly lucrative branding, The Curse’s legacy these days is allegedly one of cruelty. A regular on the convention circuit, Wil Wheaton refuses to sign anything to do with The Curse. In his 2021 memoir, Still Just a Geek, Wheaton says he was pressured into appearing in the film by his abusive parents and details a litany of horrific incidents that he and his co-star, younger sister Amy Wheaton, purportedly suffered at the hands of a crew unconcerned with their wellbeing. Wheaton’s claims include: being forced to work long hours which deliberately flouted child labour laws; being inappropriately touched on two separate occasions; and Amy having her face cut in three places by a scalpel when Fulci was displeased with the fake make-up slashes.

[1] From Arkham to The Farm by Anthony Scott King, Fangoria #66, August 1987.

[2] Anything But a Curse by Patricia O’Haire, New York Daily News, 9th September 1987.

[3] Another wrinkle to enhance The Curse’s Trans World / Empire crossover: its North American video was released by Media Home Entertainment, an outfit Empire bigwig Band established.