Welcome to Short Ends. Quick (ish) reviews of a handful (ish) of movies. Sometimes connected by a theme, sometimes not. In this second instalment, Dave charts the career of Charles B. Pierce and wonders whether he’s an unappreciated auteur or a hack who got lucky.

“Once upon a time, there was a filmmaker named Charles B. Pierce; an evolutionary throwback who never let his work be sullied by any advancements in movie-making.” [1]

I’ve always believed The Schlock Pit to be an auteur-driven website. Celebrating the enthusiasm, creativity and sheer bloody mindedness of those multi-hyphenate filmmakers who laugh in the face of adversity in order to build their own unique body of work.

The Fred Olen Rays of this world. The Jim Wynorskis. The DeCoteaus. The Leders. The Cardones.

Charles B. Pierce is certainly an auteur, but he exists on the periphery of The Schlock Pit’s Hall of Fame.

The pursuit of art versus commerce is a frequent topic of discussion on these pages. For Pierce, it frequently seemed that money was his main motivator. Every interview he gave segued onto the topic of the almighty dollar. His obsession with wealth peaked during the spring of 1977 in an article for The Shreveport Journal, where Pierce gloated over the million-dollar refurbishment of his Cross Lake mansion, its six wood-burning fireplaces, and a replica of a nine-passenger Concord stagecoach [2].

Flaunting your affluence is one thing, but Pierce’s other tic – continually insisting he was ‘a man of the people’ – is a tough contradiction to stomach.

“I make films for the majority,” Pierce told the Los Angeles Times in 1978. “They’re for Middle America. The farmers and truck drivers. I see my work to date as being the McDonald’s of motion pictures.” [3]

In terms of products barely resembling what’s advertised – and too much of it making you feel bloated and lethargic – Pierce’s analogy is credible.

But seriously, it would be churlish of me to suggest that the twelve movie career of Charles B. Pierce didn’t contain some magnificence. In among his obsessions with native American culture, period pieces and National Geographic-style travelogues, there are glimpses of a real artist – albeit confined to those moments when he momentarily lost sight of the balance sheet.

Looking back on his body of work, there’s a pang of disappointment that it wasn’t a more frequent occurrence.

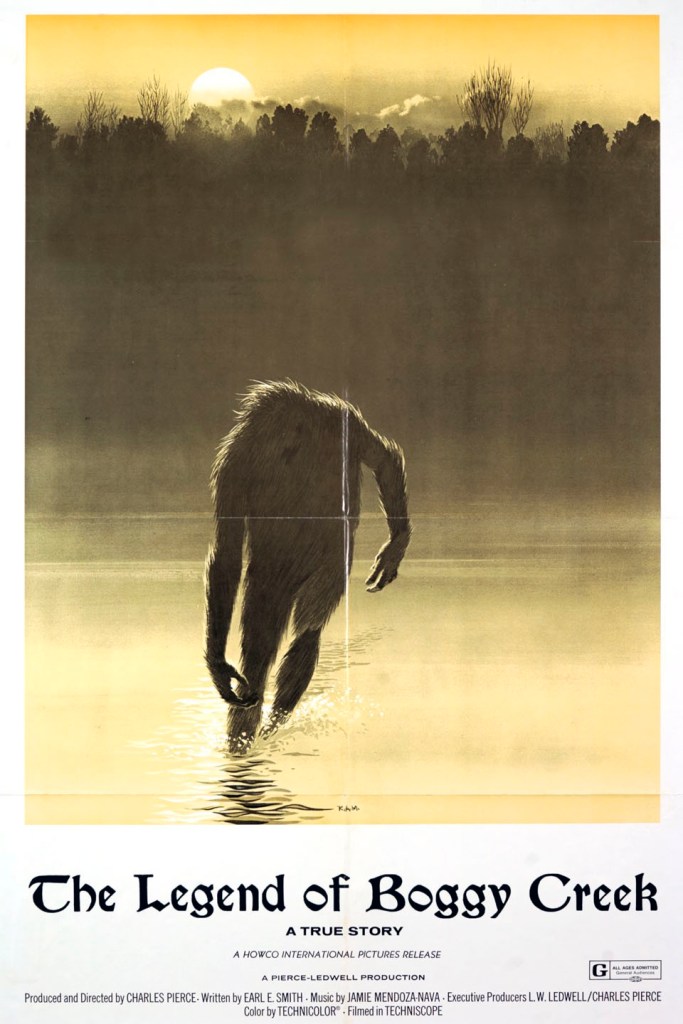

THE LEGEND OF BOGGY CREEK (1972)

Pierce spent his twenties on both sides of the camera. He worked as a director for a local television station (KTAL-TV), and occasionally he’d front-up for a live kids’ show in which he played a clown. By 1970 he’d set up his own advertising agency where he soon felt emboldened enough by his ability to wield a 16mm camera to convince one of his clients to lend him $100,000 to make a feature.

The resulting opus became Pierce’s calling card: The Legend of Boggy Creek.

Hollywood turned its nose up when Pierce tried to sell it to them, so back he came to Arkansas. He rented two cinemas to screen Boggy Creek himself and made his money back in three weeks. Within twelve months, the film – about the local legend of ‘The Fouke Monster’ – supposedly grossed more than $20million.

Recently given a much-needed restoration that was facilitated by Pierce’s daughter, Pamula, there’s a genuine beauty to be found in The Legend of Boggy Creek. The calming tone of local weatherman Vern Stierman guides us through the swamp infested wilds of Arkansas; Pierce’s nature documentary style photography is on point; and the influential docu-drama vibe brings authenticity – especially with a cast of non-actors. That said, you can only listen to so many verses of a Travis Crabtree song without losing your mind, and at times the whole shebang has a propensity to get claggier than the Fouke mudflats.

This feels like the kind of cultural touchstone that you had to experience with a degree of naivety – be it during its original release, on its initial home video run, or by chance on television [4].

Nevertheless, Boggy Creek set Pierce up for life and enabled him to make canny business decisions like partnering up with producer Joy Houck in the long-standing (and very lucrative) distribution company, Howco. The South Carolina firm had made a mint over the previous two decades by feeding low budget acquisitions like Ed Wood’s Jail Bait (1954) and The Brain from Planet Arous (1957) into drive-ins and would serve as distributor for Pierce’s next three pictures.

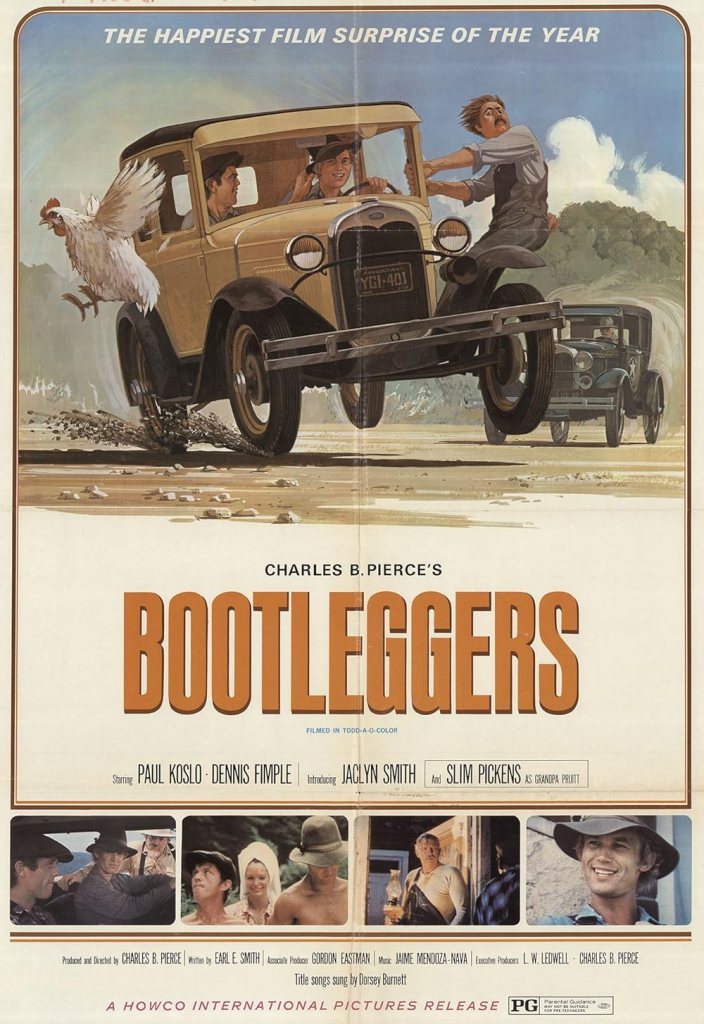

BOOTLEGGERS (1974)

Pierce is alleged to have spent some time in 1973 working as a set decorator on Jack Hill’s Coffy (1973) and Foxy Brown (1974). It doesn’t add up though. Why would a newly minted millionaire work for scale on two low-budget movies in Hollywood? He’d already cut a deal with Coffy and Foxy Brown‘s producers, AIP, for the foreign and TV distribution of The Legend of Boggy Creek, so it certainly wasn’t done to schmooze Sam Arkoff and co.

In any case, by 1974 Pierce was back behind the camera to direct Bootleggers. Pitched awkwardly between comedy and crime, the film focuses on the adventures of the Pruitts and the Woodalls: two feuding bootlegger clans causing havoc in ’20s and ’30s Arkansas.

It’s alright, but the film’s buttock-numbing, near two-hour running time dilutes what could have been a sharper and more interesting script by screenwriter Earl E. Smith. The twenty-year Navy veteran from Virginia had originally been plucked from the advertising world by Pierce for Boggy Creek and went on to pen a further four films for him.

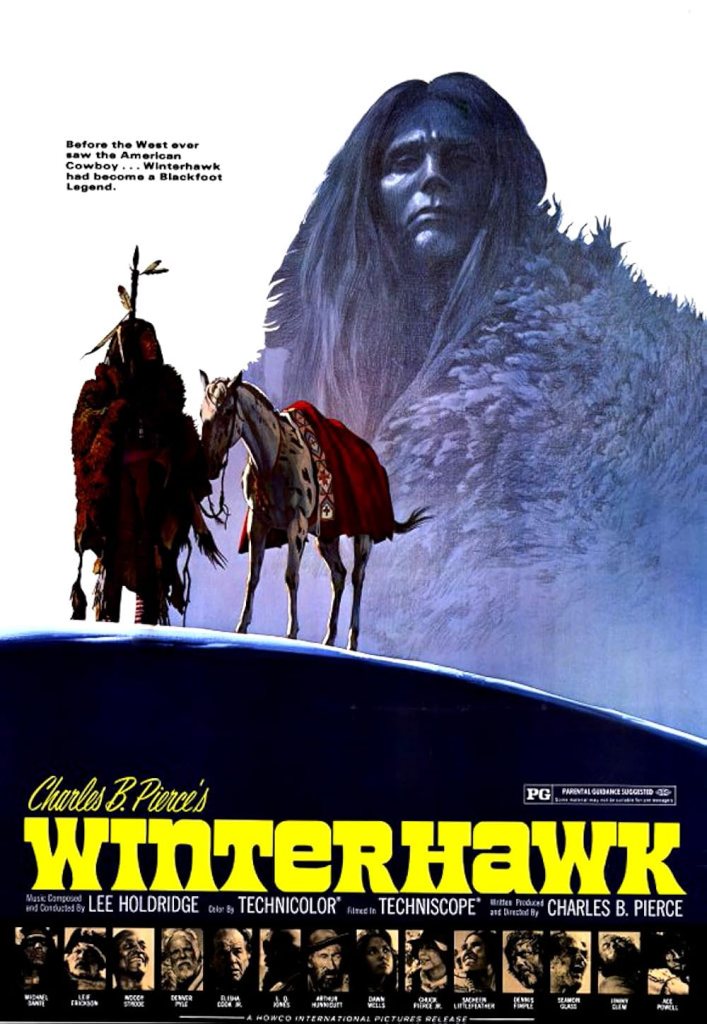

WINTERHAWK (1975)

Set in 1845 Montana, Winterhawk tells the story of a Blackfoot Chief who tries to buy a cure for his tribe’s smallpox infection. Alas, the white settlers are unsympathetic to his needs, which in turn forces the Indian Chief to resort to desperate measures.

The contradictory nature of Pierce extended beyond his ‘man of the people’ façade. Endless books on Native American culture lined the study of his lavish abode – yet when it came to including the history of this group of people in his films, it tended to be done in such a crass, heavy-handed manner. You can sense good intentions, but, ultimately, the casting of former baseball pro Michael Dante tends to undo it. When it comes to white American casting though, Pierce came up trumps. The likes of Elisha Cook, Woody Strode, and L.Q. Jones bring a real edge to Smith’s dialogue.

The pacing is prone to Pierce’s usual lack of urgency, but Winterhawk is a good-looking film, thanks in no small part to Jim Roberson in the first of four Pierce cinematographer gigs. As an aside, it’s worth checking out the supernatural shocker Superstition (1982) – one of Roberson’s best directorial assignments.

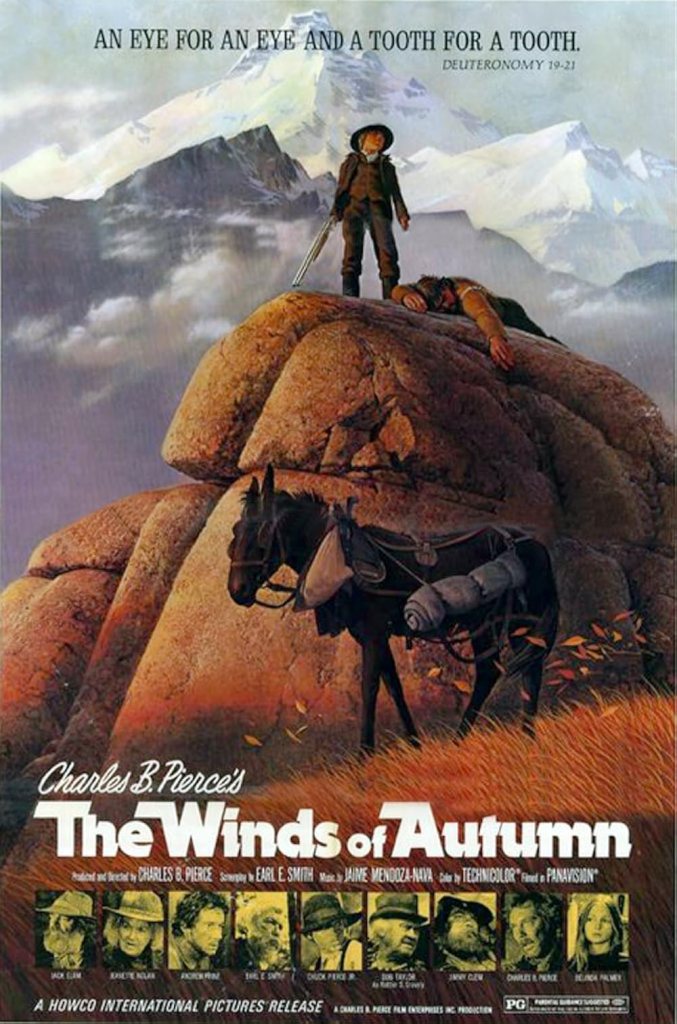

THE WINDS OF AUTUMN (1976)

Chuck Pierce is a decent actor.

Obviously, I’m referring to Pierce’s son, junior, here. We’ll take umbrage with his dad’s onscreen clowning in the next movie. But through The Legend of Boggy Creek, Bootleggers, and Winterhawk, Pierce’s blond-haired sprog cut quite the assured figure in a variety of kid parts – though it’s The Winds of Autumn where the lad really shines.

The younger Pierce plays Joel Rigney: an eleven year-old Quaker boy who sets out on his own to seek revenge against the gang of outlaws who murdered his family. Keeping a watchful eye on him is the protective Mr. Pepperdine, played by the films’ screenwriter, Earl E. Smith.

Again beautifully photographed by Roberson – albeit somewhat further north, amid the lush landscapes of Kalispell, Montana (where it also premiered in February ’76) – The Winds of Autumn also marks the first of four pictures that Piece made with the force of nature that is Jack Elam.

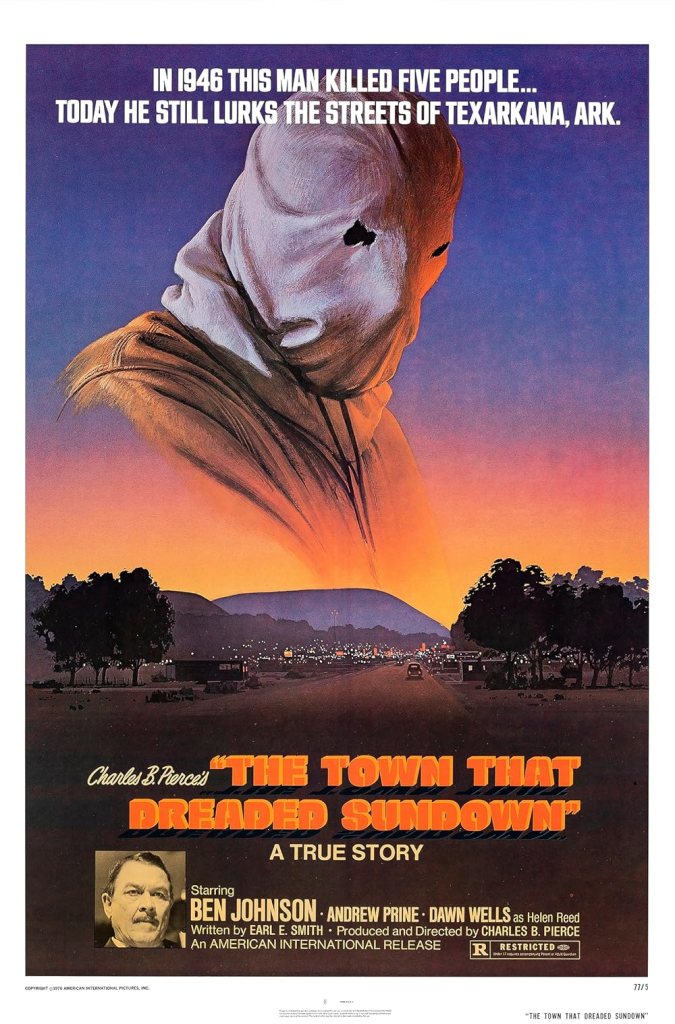

THE TOWN THAT DREADED SUNDOWN (1976)

”It’s not my favourite show,” mused Charles B. Pierce to the West Bank Guide, barely two weeks after the premiere of The Town That Dreaded Sundown. “But you won’t be bored in it. I know a lot about pacing, and proper pacing means the difference between a good picture and a bad one. My shows move!” [5]

The less said about pacing the better in terms of Pierce’s movies – but The Town That Dreaded Sundown really should have been his favourite.

It’s certainly his best.

Based on the Texarkana Moonlight Murders – a series of violent crimes committed in 1946 by an unidentified male referred to as ‘The Phantom Killer’ – Pierce’s film wastes precious little time in introducing us to the hooded perp preying on couples trying to get jiggy in local beauty spots. In a town growing ever more paranoid, deputy Andrew Prine and flashy lawman Ben Johnson find themselves in a race against time to solve the case before the killer strikes again.

Possessing one of the great opening sequences of ’70s horror cinema, The Town That Dreaded Sundown has you in the palm of its hand from the get-go. The city and surrounding area of Texarkana – named because of the way it straddles the Arkansas and Texas state line – is a compelling location, and Pierce’s calling card of non-actors in key roles adds to the fascinating pseudo-documentary vibe. Admittedly the director tends to over-egg the pudding when it comes to replicating the kill sequences, specifically the notorious trombone bit (inflicted on his twenty-year-old, real-life bride-to-be, no less), but they still pack a punch. Pierce’s ‘comedic’ turn as the hapless patrolman ‘Sparkplug’ Benson, however, is unpardonable.

Even after half a century, I’m still not convinced The Town That Dreaded Sundown receives the acclaim it deserves. Having said that, its reputation is considerably loftier than it was upon its release. Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times billed it as “this week’s trash picture”, before going on to bemoan that “there’s no sense of period, no suspense, no nothing” [6]. The local rags were just as unforgiving, with Elston Brooks in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram blasting it as “the most poorly acted film in recent memory, and certainly the most ludicrous.” [7]

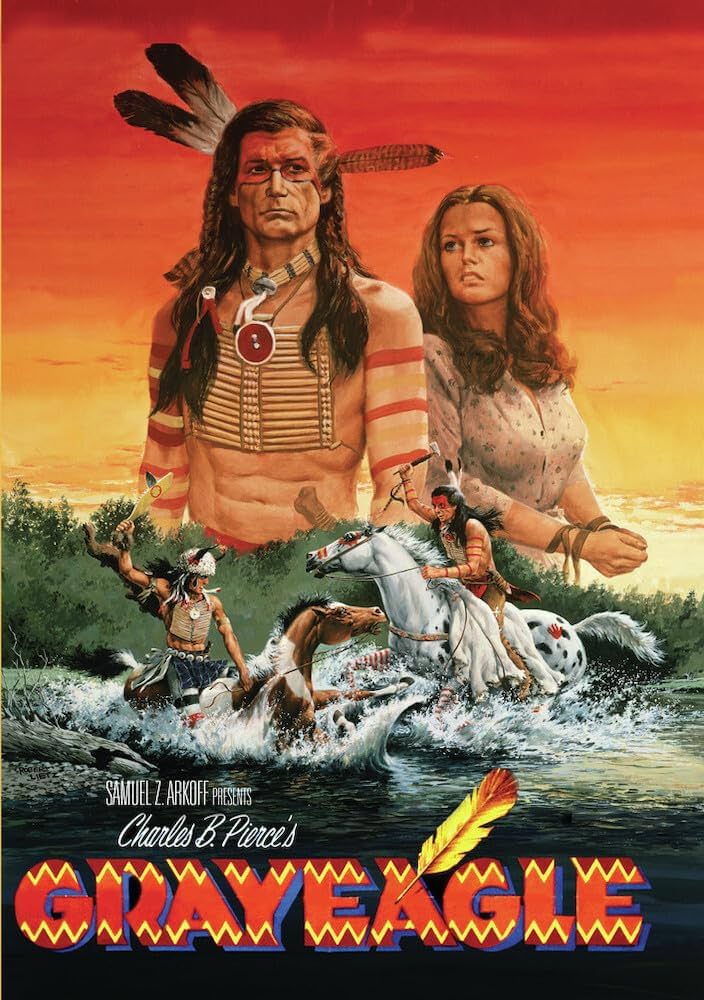

GRAYEAGLE (1977)

There’s a sense that the dawn of ’77 was the moment the wheels started to loosen on the Charles B. Pierce juggernaut. Everything seemed a little less focused. An announcement was made about the construction of a movie studio in Shreveport that never came to fruition, and production of ‘Road to Appomattox’, a feature about the final fourteen days of the Civil War, fell by the wayside.

Sacred Ground was also mentioned during this time, potentially as a project for an idol of Pierce’s, John Wayne, off the back of The Duke’s great notices for The Shootist (1976). In the end the filmmaker went ahead with a picture that’s certainly adjacent to Wayne’s legacy:

Grayeagle.

It doesn’t take a scholar of Pierce’s work to sense his adoration of John Ford. Indeed, when Lane Crockett interviewed him for The Shreveport Journal prior to Grayeagle‘s shooting, Pierce’s passion for the iconic director seeped from the page:

“He is intense when he speaks of Ford and what he accomplished,” wrote Crockett. “There is no uncertainty that Pierce, deep inside, is striving for the same thing, although he shies away from committing himself.” [8]

Greyeagle is Pierce’s variant on The Searchers (1956). Set in Montana territory in 1848, it tells the story of a young Cheyenne warrior (played by the decidedly non-Native American, Alex Cord) who kidnaps the daughter (Lana Wood, failing to harness her sister’s performance from ‘56) of a frontier man (Ben Johnson).

It’s a valiant effort from Pierce, despite the obvious shortcomings. The creative dream team of cinematographer Jim Roberson and composer Jaime Mendoza-Nava elevate the film, but poor casting and a predictably saggy pace knock it down to a notch above bang average.

THE NORSEMAN (1978)

Despite Pierce owning a lucrative chunk of distributor Howco, it soon became clear to him that if he wanted to be more of a player in the movie business, then he would have to utilise the services of a company who could hit a little harder.

Enter American International Pictures.

Sam Arkoff’s outfit had long been synonymous with films at the lower end of the budgetary scale, although a desire to move away from that pigeonhole was frequently met with disappointing box office. In terms of Pierce, they’d already distributed The Town That Dreaded Sundown and Grayeagle – but for The Norseman they expressed a desire to add some money to the production pot.

$3million was the budget, which was the most Pierce ever had to work with. Add Lee Majors in a starring (and producing) role, fresh off the back of the immense success of The Six Million Dollar Man, and surely you have a recipe for success, right?

Wrong.

Movies were changing – but Pierce didn’t seem capable of change. Jaws (1975) had changed the face of motion pictures forever, yet here was Pierce standing on a swampy shoreline in Tampa, Florida, with a Viking longboat sailing past, manned by Cornel Wilde.

The Norseman is a terrible film, and Pierce’s worst by far. Gary Arnold of The Washington Post said that “the only thing The Norseman is good for is a derisive laugh” [9]. Pierce hoped for better, predicting a whopping $50 to $60million at the box office, and Majors was optimistic too, negotiating a tidy salary of half a million and ten percent of the box office.

The Norseman opened on 5th October 1978 and tanked with a gross of only $1million. Five days after its cinema debut, the production company, Filmways Inc., signed an accord in principle to buy AIP.

“We’ve been the Woolworths of the movie business, but Woolworths is being outpriced,” Arkoff told the Wall Street Journal [10].

THE EVICTORS (1979)

In many ways The Evictors seems like Pierce’s reset. After time away in Montana filming Grayeagle and Florida for The Norseman, his return to horror brought him back home – albeit twenty-five minutes west of Shreveport, to Jonesville, Texas. New writing partners came aboard in Gary Rusoff and Paul Fisk (who’d been a cameraman on Winterhawk), and a new director of photography in Chuck Bryant. The result is an impressive one, with The Evictors an ideal companion to The Town That Dreaded Sundown.

Set four years before Sundown, the opening gambit assures you that the following film is based on a true story. It concerns Ben and Ruth Watkins (Michael Parks and Jessica Harper), who have purchased a small rural property but remain blissfully ignorant of its violent history. As their stay continues they become increasingly aware of the fate befallen by the house’s former owners, and are suspicious of a presence that seems intent on forcing them to leave.

The Evictors is very much an old school horror, toning down the level of violence that Pierce exhibited in Sundown. Suspense and atmosphere fill the gaps and do so with great effect. It helps if you have the talent to execute it, though; but with Parks, Harper, and an excellent performance by Vic Morrow, this is one picture where the casting gods worked their magic for Pierce.

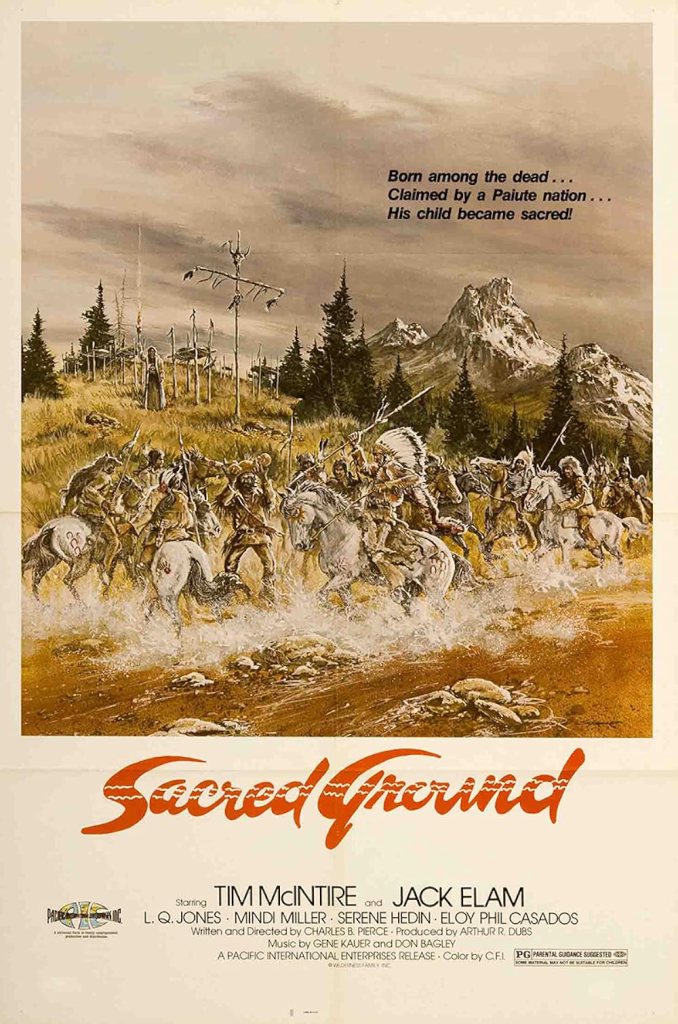

SACRED GROUND (1983)

During the giddy heights of the Sundown era, Pierce was mulling over the possibility of making two films a year. Barely half a decade later, the Pierce production line had ground to a halt, his luxury mansion in Shreveport was on its way to becoming a distant memory, and Charles Bryant Pierce found himself living in Carmel, California, and cosying up to Clint Eastwood.

That friendship led to Eastwood snagging Pierce’s treatment for the film that eventually became Sudden Impact (1983). Since, Pierce always insisted that he’d created Dirty Harry’s infamous line, “Go ahead, make my day”. The accuracy of that claim is debatable, not least because the filmmaker spent his career incorporating increasingly fanciful boasts into the interviews he gave.

In any case, L.A. never really agreed with Pierce (“I only like to be there long enough to strike a deal and get out” he once said), so, by 1982, he went north to Oregon to film the long-gestating Sacred Ground.

It’s 1861 and mountain man Matt Colter (Tim McIntire) and his Native American wife move into a vacant and partially built cabin in the hope of building a new life together. Unfortunately, they’re unaware of the fact that their new abode is built on a Paiute burial site, and them living there will unleash a violent and ultimately tragic dispute.

This feels like a more mature film for Pierce. The structure of it is more balanced and well-paced in comparison to many of his westerns from the ‘70s, and there’s an unmistakable air of a filmmaker trying to prove himself. Jack Elam – as with any film – is a pure joy to watch, while McIntire can’t help but cut a tragic figure (which morbidly suits the character) in the final film before his premature death. Oregon’s lush snowy backdrop serves the movie nicely too.

BOGGY CREEK II: AND THE LEGEND CONTINUES (1983)

Pierce had a self-confessed loathing of sequels, and for the best part of a decade refused to even consider coming back to the world of the Fouke monster. In the meantime, his good friend Tom Moore made Return to Boggy Creek (1977); his distribution partner Joy Houck made The Creature from Black Lake (1976); and even his star attraction in The Norseman, Lee Majors, did a Bigfoot-themed episode of The Six Million Dollar Man.

Perhaps the time was right?

Oregonian distro Pacific International didn’t do wonders with Sacred Ground, and it came and went with barely a whimper. Pierce was swiftly running out of options to keep his film career afloat. As he told The Edmonton Journal, “I have a certain amount of risk money set aside to continue, but if I lose that, I retire.” [11]

With Boggy Creek II: And the Legend Continues, he certainly did his level best to accelerate that threat.

Etched into infamy by the irritants at Mystery Science Theater 3000, Pierce is arguably the chief facilitator of his own downfall. By casting himself, his wife, and his son as three of the four leads in this maligned sequel, he’s effectively pinned his portrait to a dartboard and set about handing arrows to anyone who fancied a shot.

I don’t think Boggy Creek II is anywhere near as bad as it’s made out to be. Granted, it stands on the bottom few rungs of the Pierce filmography, but there’s an affection to be found from heading down to the swamps of Arkansas one more time. Pierce Sr.’s blowhard character might come across as a superior know-it-all – but at least he’s being authentic!

Pierce cranked up the Howco name one last time to handle the film’s distribution, with a premiere in Shreveport on 16th December 1983. Business was slow, though. Boggy Creek II was hampered by some savage reviews, and it bypassed the west coast altogether, only reaching New York on the east coast two years later, in December ’85.

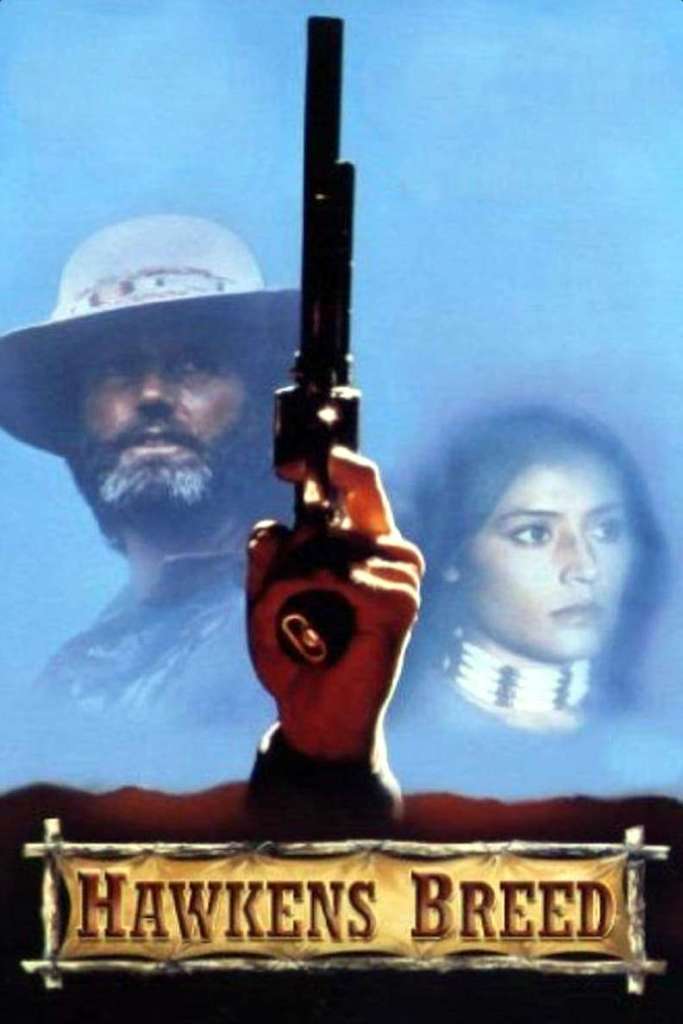

HAWKEN’S BREED (1987)

Predictably the Pierce camp fell silent for a few years in the wake of Boggy Creek II: And the Legend Continues. By spring 1986, however, the director had relocated once more, this time shuffling east of the Arkansas border to Tennessee and the rural city of Dover.

“I have several scripts that I plan to get to soon,” he boasted to The Stewart-Houston Times, “But I can’t tell you about them because there are just too many other filmmakers out there looking for good ideas.” [12]

First on the list for Pierce was Hawken’s Breed. Originally written as a vehicle for Clint Eastwood (“His political ambition prevented a collaboration,” chuntered Pierce), the project eventually tumbled to Peter Fonda, who took the part of the eponymous Hawken: a rugged drifter who comes to the rescue of a young Shawnee woman called Spirit (Serne Hedin).

Pierce clearly wasn’t in the mood to risk any more money than he needed to, and as a result Hawken’s Breed comes across as cheap and poorly developed. Full of limply scored moments where nothing happens, Fonda sleepwalks through the bulk of it and Jack Elam feels lost without a real character to sink his teeth into.

Prior to the cameras rolling, Pierce boasted about how major studios were keen on the film, and that ‘big name’ Nashville people were lined up to record a ballad for the soundtrack. In the end – and after Pierce was allegedly denied final cut – Hawken’s Breed went straight-to-video three years after it wrapped [13] and its title song was warbled by Mike Di Napoli, whose claim to fame is a track on the Dance Academy (1987) OST.

RENFROE’S CHRISTMAS (1997)

Chasing the Wind (1998) is listed as Pierce’s final film, but aside from some very foggy screenshots on IMDb, it doesn’t seem to have been released on physical media or had any airings on television. Thus we’ll end this overview in the doldrums of shot-on-video family fare with Renfroe’s Christmas (aka ‘Renfroe’s White Christmas’).

It’s a turgid affair. Ugly to look at and prone to lapses in quality control (like the sight of a car park lurking in the background of what’s meant to be 1930s rural Louisiana). Pierce seems to be a director-for-hire on this show – a favour to producer Jim McCullough, maybe? After all, the two men had crossed paths on multiple occasions over the previous decades, with Pierce even taking an acting role in McCullough’s lesser-seen sci-fi-comedy-western hybrid, The Aurora Encounter (1986).

The less said about this reunion, though, the better.

Renfroe’s Christmas is a forgettable end to a maddening, difficult, but unique and wholly unforgettable career.

[1] Film Reviews by Chris Gladden, The Roanoke Times, January 1985.

[2] He Built ‘A Pretty Nice Home’ by Betty Paul Bigner, The Shreveport Journal, April 1977.

[3] Lee Majors’ Image Switch by Clarke Taylor, Los Angeles Times, March 1978.

[4] The Legend of Boggy Creek premiered in the U.K. at 6:00pm one evening in 1981 on BBC2.

[5] Million Dollar Country Boy, West Bank Guide, January 1977.

[6] ‘Sundown’ Mired in Morbidity by Kevin Thomas, Los Angeles Times, 5th March 1977.

[7] Town May Dread Film as Much as Sundown by Elston Brooks, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 2nd February 1977.

[8] Charles B. Pierce by Lane Crockett, The Shreveport Journal, 8th April 1977.

[9] The Scowling, Bionic ‘Norseman’ With a Southern Accent by Gary Arnold, The Washington Post, 1st August 1978.

[10] Filmways Inc. Signs Accord in Principle for Movie Maker, Wall Street Journal, 10th October 1978.

[11] From Rags to Riches in Movies by Bob Gilmour, The Edmonton Journal, 14th June 1975.

[12] Pierce Seeking Blond-Haired Blue-Eye Boy for Hawken Role by David R. Ross, The Stewart-Houston Times, 16th April 1986.

[13] Although it was briefly four-walled in Iowa for a week.