Welcome to Short Ends. Quick (ish) reviews of a handful (ish) of movies. Sometimes connected by a theme, sometimes not. In this debut instalment, Matty delivers a potted history of Full Moon boss Charles Band’s ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s directorial assignments.

Generally thought of as a producer – a B-movie mogul, operating in the manner of an old fashioned studio boss – Charles Band’s actual directorial assignments are a seldom discussed topic. The awesome Trancers (1984) aside, the bulk of the Full Moon boss’ signature texts — Tourist Trap (1979), Ghoulies (1985), Re-Animator (1985), Puppet Master (1989) etc. — are Charles Band productions rather than Charles Band films.

In the interest of redressing the balance, here is a whistle-stop tour of the pictures Band called ‘action!’ on between 1973 and 1999.

LAST FOXTROT IN BURBANK (1973)

Charlie’s first movie.

A spoof of Bernardo Bertolucci’s controversial sex drama Last Tango in Paris (1972) almost as painful as its groan-inducing title. But hey, everybody’s got to start somewhere. And for all Last Foxtrot in Burbank gets wrong (rubbish script, early Band regular Michael Pataki’s obnoxious Brando impression), it’s in focus and relatively fast paced.

In terms of theme and content, the film points to the T&A romps Band (as producer) pursued on and off throughout his career (Cinderella (1977), Fairy Tales (1978), Meridian, the Torchlight Entertainment and Surrender Cinema fare). However, given Band spent years either denying Last Foxtrot’s existence (certain prints are credited to director ‘Carlo Bokino’) or minimising his input, much in the same way he hid his involvement with Surrender, the film is more of an insight into his surprisingly prudish attitude towards erotica than anything else. Still, Last Foxtrot remains historically fascinating, what with it supposedly being financed by several shady individuals; it being edited by a pseudonymous John Carpenter (as ‘John T. Casino’); and its once ‘lost’ status. Note the bunny ears. Reading between the lines, Last Foxtrot’s vanishing seems deliberate. According to legend, Band ordered the destruction of the film after a poorly received L.A. premiere on 26th October 1973. Yet despite such claims, Last Foxtrot was playing adult theatres deep into the ‘80s. Its last documented engagement was at XXX entrepreneurs the Mitchell Brothers’ Bijou theatre in San Francisco on Thursday 3rd November 1988, in a triple bill with Chuck Vincent’s Visions (1977) and Michael Zen’s Reflections (1977).

For what it’s worth, Band’s reluctance to claim Last Foxtrot in Burbank as his own has softened in the intervening decades, particularly after the film’s negative was rediscovered in the UCLA archives in 2010. Now Band, per his kink for numbered output, humorously refers to it as ‘Full Moon 0’.

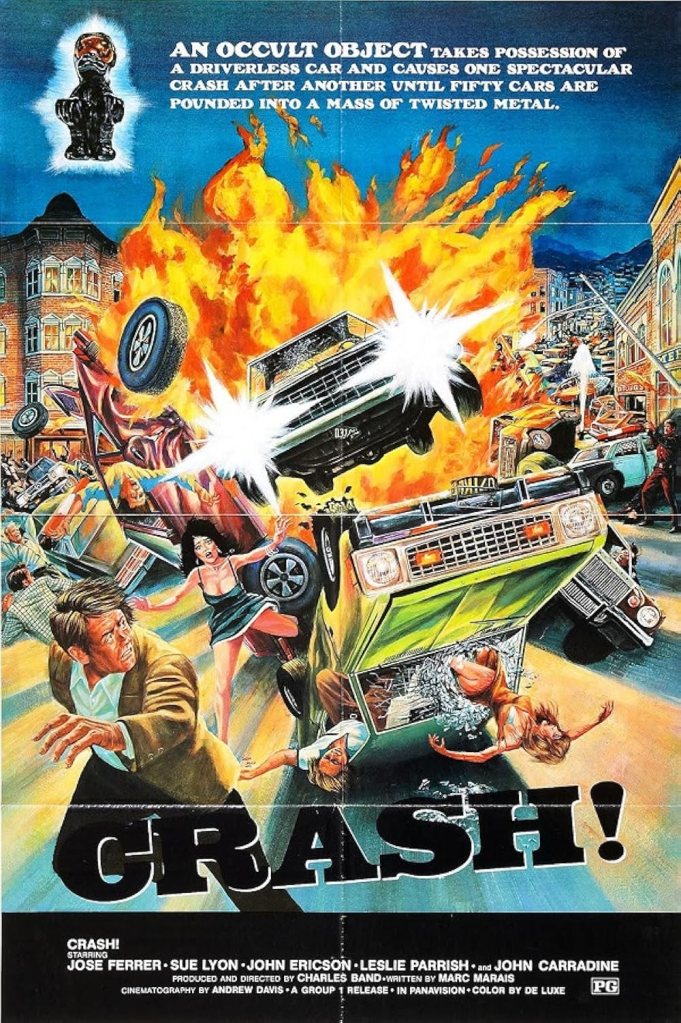

CRASH! (1977)

Like Jack Starrett’s Race with the Devil (1975), Crash! — Band’s ‘official’ directorial debut — bridges the gap between two of the ‘70s most potent cinematic trends — road movies and supernatural horror — and was allegedly slung together to capitalise on Universal Pictures’ then upcoming marriage of the two, The Car (1977).

Endearingly of its decade in manner, look and soundtrack, Crash! is defined by incredible kamikaze stunt work (coordinated by Von Deming) that transcends the chump change budget. The plentiful scenes of fiery vehicular violence are glorious (“A symphony of fireballs!” says Band). They’re moments of real spectacle, and the film is laced with a seductively weird vibe. Sadly, despite how visceral and effective Crash! is visually and atmospherically, its dramatic punch is hindered by the script’s lack of emotional resonance. And, really, the story doesn’t make much sense. It’s something to do with a cantankerous old bugger (José Ferrer) trying to kill his gorgeous younger wife (Sue Lyon) while a spooky, driverless car wreaks havoc on the California backroads, powered by a mysterious amulet. Nevertheless, Crash! is certainly an experience, and a strong contender for the title of Band’s kookiest movie — no easy feat.

A favourite of Band disciple David DeCoteau – who homaged the film with his own car caper, Speed Demon (2003) — keen-eyed viewers will notice the cast and crew overlap with Band’s father Albert’s Zoltan… Hound of Dracula (1977), which lensed shortly beforehand. A lot of the crew also toiled with Band on Mansion of the Doomed (1976) (the authorised ‘Full Moon No. 1’), and several went on to ply their trade on Cinderella and Fairytales suggesting that, even pre Empire and Full Moon, the impresario liked the idea of creating a filmmaking family.

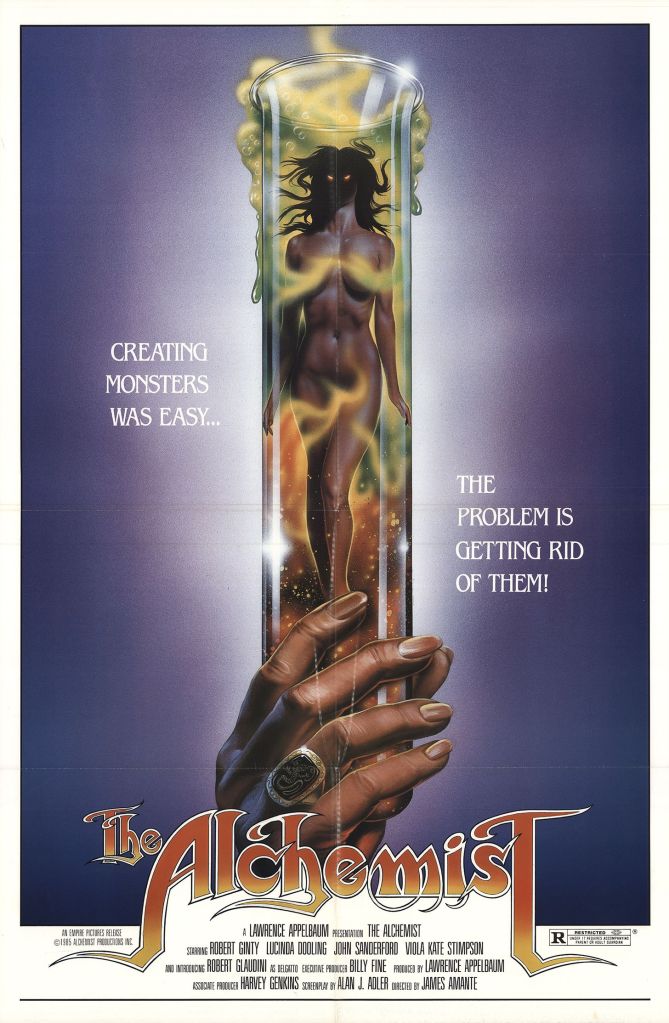

THE ALCHEMIST (1983)

Produced by exploitation veterans Lawrence Appelbaum and Billy Fine, The Alchemist was lensed before Band’s fourth directorial assignment, Parasite, but released after it. A stodgy and messy movie, The Alchemist isn’t entirely without merit. Band crafts several eye-catching images and the peculiar vibe he fosters is almost – almost – as captivating as Crash!’s unique strain of crazy.

A bored-seeming Robert ‘The Exterminator (1980)’ Ginty stars as Aaron: a glum fellow destined to walk the earth — well, California woodland — as a man-beast after falling afoul of an evil sorcerer named DelGatto (Robert Glaudini).

A troubled production, The Alchemist’s difficult making and tardy distribution presumably cemented Band’s belief in doing things his way. Brought in at the eleventh hour to replace original director Craig Mitchell (co-director of Don Coscarelli’s pre-Phantasm (1979) dramedy Jim, The World’s Greatest (1975), and future co-scripter of creature feature Komodo (1999) and road shocker Highwaymen (2004)), the project stands as Band’s sole gun-for-hire gig to date. That said, there are auteur licks. Several plot points — Curses! Romance! Magic! Monster making! Time shifts! Revenge! — prefigure similar elements in a number of Band’s later, better epics: The Dungeonmaster, Trancers, Doctor Mordrid, Head of the Family, Hideous!, The Creeps, Dr. Moreau’s House of Pain (2004), Skull Heads (2009), and, most noticeably, Meridian.

As with Last Foxtrot in Burbank, Band hid behind a pseudonym (‘James Amante’) when The Alchemist finally started its U.S. theatrical run in May 1985. He did, though, distribute the film through Empire. We Brits got it a little earlier, in mid-’83, and Band was fully credited on prints and advertising materials.

PARASITE (1982)

See here.

METALSTORM: THE DESTRUCTION OF JARED-SYN (1983)

While not what you’d call a conventionally great movie, Metalstorm: The Destruction of Jared-Syn deserves better than the snarky ‘so bad it’s good’ reputation it’s cultivated among – urgh – the ‘trash cinema’ and RiffTrax crowds. An unashamed mish-mash of Star Wars (1977), Mad Max (1981), Conan: The Barbarian (1982), and just about any other sci-fi and fantasy flick popular at the dawn of the ‘80s, the script is garbage (a criticism that can be levelled at writer Allan J. Adler’s preceding Band joints, The Alchemist and Parasite), but the ambition and scope of the film – particularly in relation to its budget – is genuinely impressive. Chronicling the battle between a space ranger (Jeffrey Byron) and his titular intergalactic nemesis, Jared-Syn (Michael Preston), Metalstorm is a fun, easygoing watch packed with imaginative side characters (the half-cyborg Baal is fabulous); giddy pantomime performances (shout out to Richard Moll and Tim Thomerson — his debut Band appearance); and a Saturday matinee swagger.

Band’s second 3D flick following Parasite, the helmer and his trusted cinematographer, Mac Ahlberg, really get into the swing of the format here. Yes, it’s still corny and gimmick driven, what with objects continuing to get flung at the screen. This time, however, there’s a stronger emphasis on using 3D as a way to bring us deeper into Metalstorm’s quasi-mystical sci-fi western world – a domain Band, as producer, returned to over a decade later via cowboy n’ aliens potboilers Oblivion (1994) and Backlash: Oblivion 2 (1996). The latter even appropriated Metalstorm’s ace tagline: “It’s high noon at the end of the universe!”.

Metalstorm was acquired for U.S. distribution by Universal. The major had spent a fortune kitting out cinemas with 3D projectors for Jaws 3D (1983) and figured Metalstorm could bounce off the back of it.

As an aside, Band originally intended to shoot Ghoulies in 3D before scrapping the idea.

THE DUNGEONMASTER (1984)

Shot straight after Metalstorm, their productions broken up by a weekend, The Dungeonmaster marks the maiden voyage of Band’s beloved ‘80s outfit, Empire International Pictures.

In a sense, the film’s the centre of Band’s entire orbit.

A fantasy anthology, ostensibly designed to cash-in on Tron (1982) and the increasing popularity of roleplaying game Dungeons & Dragons, the plot sees a computer programmer (Metalstorm’s Jeffrey Byron) going toe-to-toe with an evil sorcerer (erm, Metalstorm’s Richard Moll) in a series of challenges. Band tackles the wraparound and a segment called ‘Heavy Metal’ (featuring rock band W.A.S.P., who’d later provide the theme song for Ghoulies II (1987)). The other segments are helmed by Rosemarie Turko, John Carl Buechler, ‘Steve Ford’ (in actuality Byron’s brother, Steve Stafford), Peter Manoogian, and Ted Nicolaou and were a proving ground; a way for Band to gauge if they had the chops to direct a feature. Buechler, Manoogian, and Nicolaou became an integral part of Band’s circle, belting out Troll (1986), Eliminators (1986), TerrorVision (1986) and more between them. Ergo, I’d say the experiment was a success…

As a whole, The Dungeonmaster is technically adroit (Mac Ahlberg’s photography is stunning, especially in the scenes set in Moll’s hellish realm) and tremendous fun, if somewhat repetitive.

Also known as ‘Digital Knights’ (the title it was initially nudged into U.S. cinemas as) and ‘Ragewar’.

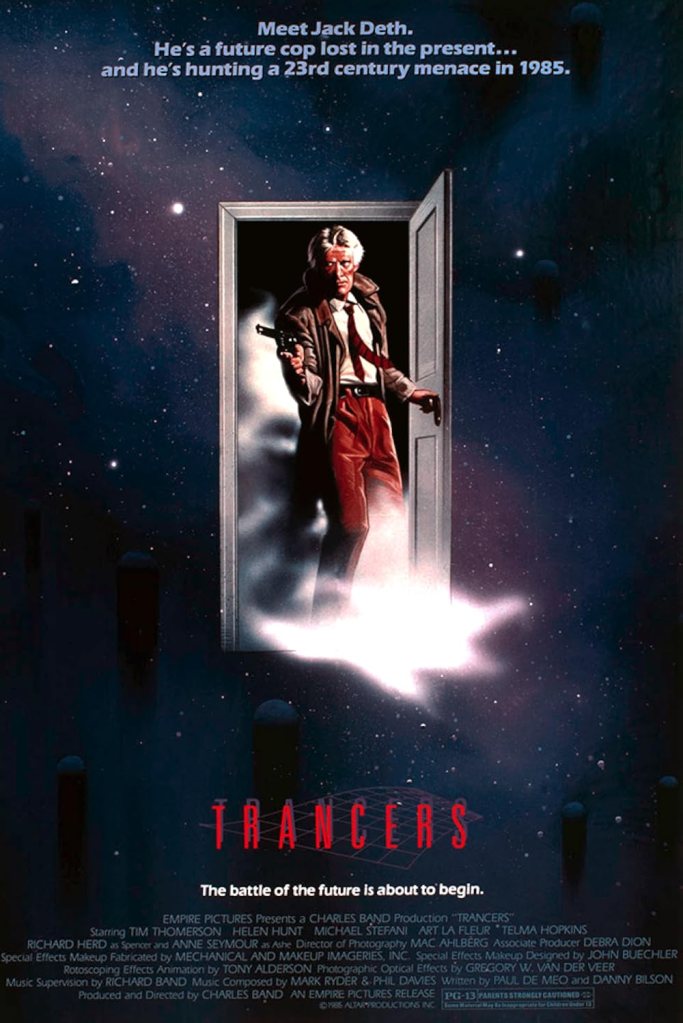

TRANCERS (1984)

See here.

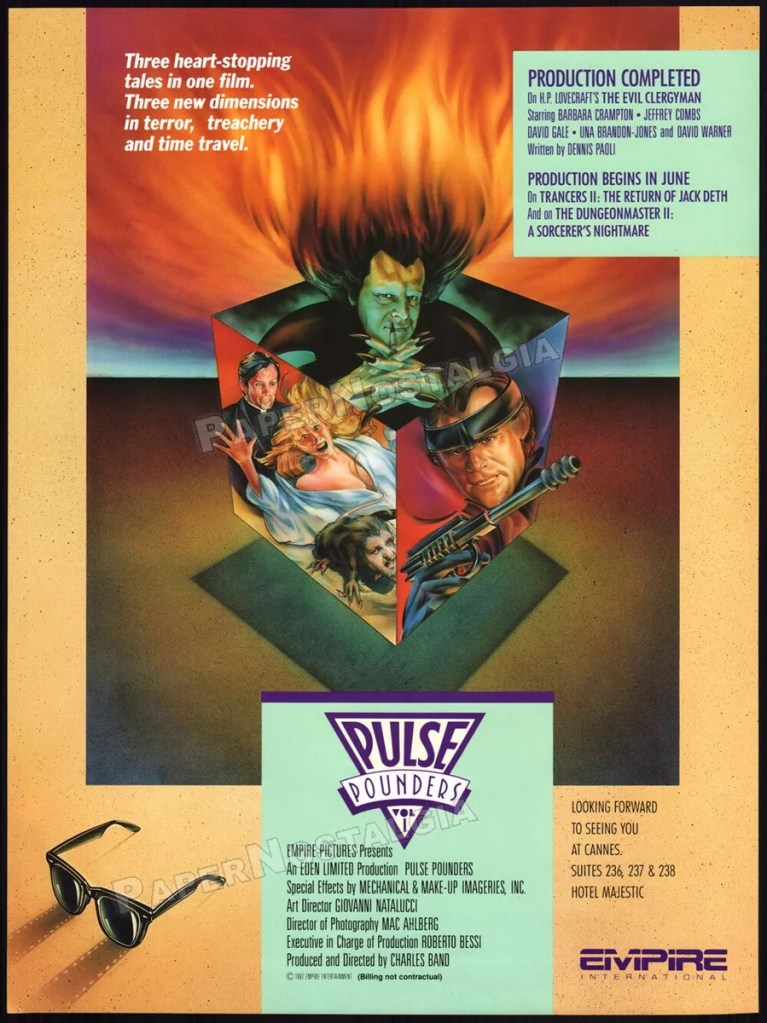

PULSE POUNDERS (1988)

Intended as the start of a series of anthologies meant to sequelise various Empire properties, Pulse Pounders fell victim to the company’s financial woes and was thought lost for decades. In that time, it achieved something of a mythic status among fans of Band’s wares, rivalling the unmade ‘Decapitron’ in the what-could’ve-been stakes. Though one of Pulse Pounders’ segments, ‘The Dungeonmaster II: A Sorcerer’s Nightmare’, remains MIA, tape dupes of the other two – ‘The Evil Clergyman’ (a H.P. Lovecraft tale a la Re-Animator and From Beyond (1986)) and the self-explanatory ‘Trancers: City of Lost Angels’ (née ‘Trancers II: The Return of Jack Deth’) – were found during a Full Moon office clearout in 2011 and have since been made available on disc and streaming.

Of them, ‘The Evil Clergyman’ is the superior sequence. While undoubtedly lacking Empire Lovecraft specialist Stuart Gordon’s touch, Band delivers a competent and atmospheric facsimile anchored by a decent script (courtesy of Gordon acolyte Dennis Paoli); sturdy production values; and a fine cast (Re-Animator’s Jeffrey Combs, Barbara Crampton and David Gale, accompanied by David Warner as the eponymous unholy man).

‘Trancers: City of Lost Angels’ is a tepid affair hindered by the limitations of its story – in which the gruff future cop, Jack Deth, takes on a female assassin – having to fit a short-form narrative and the film’s sound stage execution. But hey, as if it matters. The pleasure is seeing the gang again, with Band, Tim Thomerson, Helen Hunt, Art LaFleur, Telma Hopkins, and scribes Danny Bilson and Paul DeMeo treating the project as a lark. Considering Pulse Pounders looked like the only follow-up we’d ever get to Trancers at the time of its making, that kind of thigh-slapping jocularity counts for something in my book.

Band recycled the Pulse Pounders imprimatur for a kids’ label in the late ‘90s.

MERIDIAN (1990)

Meridian is funny if you think about it. As mentioned in my notes on Last Foxtrot in Burbank, Band has always been prudish about erotica – and yet this ultra-sexy shocker nestles at the top end of his directorial resume. It’s a dreamy sensory blitz of a film. Well told, well played, and very well made – what The Alchemist should have been.

Cast just prior to Twin Peaks exploding across TV screens, Sherilyn Fenn – already white-hot in video circles due to her eye-popping turn in Zalman King’s Two Moon Junction (1988) – stars as an American girl abroad, caught in an ancient supernatural feud between twin brothers (Malcolm Jamieson). One is an evil warlock, the other is – wait for it – cursed to transform into a man-beast in the throes of passion. Horror, humping (Fenn and Full Moon favourite Charlie Spradling supply plenty of derma), and deliciously hammy performances from Phil Fondacaro, Hilary Mason, and Vernon Dobtcheff ensue.

As proposed by author and Schlock Pit pal Dave Jay in It Came From the Video Aisle!: Inside Charles Band’s Full Moon Entertainment Studio, Meridian – the third film to bear the Full Moon handle after Puppet Master and Shadowzone (1990) – can be seen as an Empire goodbye. It’s the last Band production to feature such talent as scripter Dennis Paoli; production designer Giovanni Natalucci; cinematographer Mac Ahlberg; and editor Ted Nicolaou all together – rather than, say, one or two of them here and there. Bolstering Jay’s intriguing theory are Merdian’s spectacular Italian locations. Italy was a key ingredient to many an Empire romp, thanks to the shingle’s studio in Rome. And alongside the sorely under-seen Catacombs (1988), Meridian ranks among Band’s most authentically Italian ventures. The country factors into the story, and the lion’s share of this gorgeously photographed piece was shot in Band’s own castle, Castello di Giove (which subsequently appeared in The Pit and the Pendulum (1991) and the superficially similar Castle Freak (1995)). Meridian’s stirring otherworldly ambience, meanwhile, is augmented by Band’s sublime use of the remarkable Sacro Bosco, ‘The Park of Monsters’, in Bomarzo.

A canny but sus bit of trivia:

Band reckons that the man-beast’s creature suit was a prototype FX wiz Gregg Cannom rustled up for the werewolf scenes in Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), tweaked to avoid detection. I think that’s either a false memory or more self-aggrandising mythology on Band’s part because none of the dates match. Meridian was in the can before Winona Ryder passed Francis Ford Coppola the first draft of Dracula’s script. If anything, it was likely a Cannom creation left over from Fox TV show Werewolf.

Also known as ‘Phantoms’, ‘Kiss of the Beast’, ‘Meridian: Kiss of the Beast’, and, on streaming, ‘The Ravishing’.

CRASH AND BURN (1990)

See here.

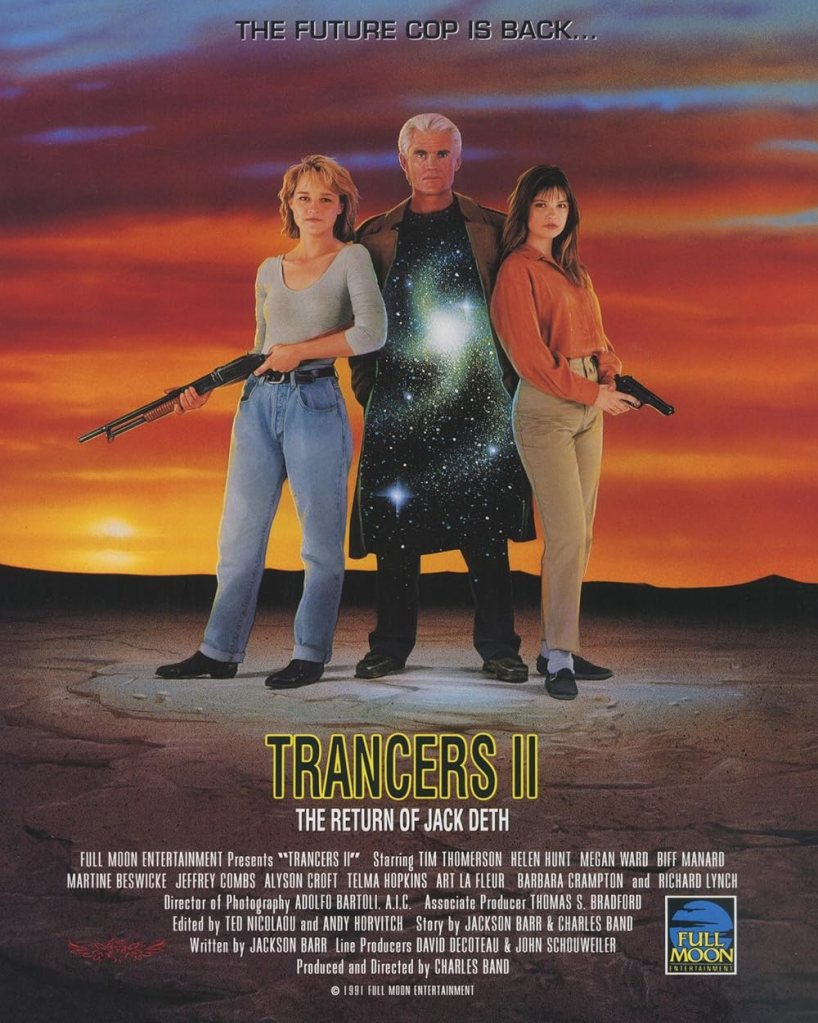

TRANCERS II (1991)

The future cop is back!

Alas, it’s with a splutter, not a bang.

Having wangled Trancers’ rights as part of his Empire severance package, Band announced Trancers II – which, on most home video art, sports the same subtitle originally used on Pulse Pounders’ mini-sequel, ‘The Return of Jack Deth’ – in his inaugural Full Moon slate circa late ‘88. Then, the first film’s scripters, Danny Bilson and Paul DeMeo, were attached; both writing, Bilson directing. By the time Trancers II was given the go-ahead by Full Moon’s sugar daddy, Paramount, Bilson and DeMeo were busy with The Rocketeer (1991) over at Disney, leaving the script to be penned by Jack Canson (aka ‘Jackson Barr’, Subspecies (1991)) and the reins picked up by Band.

Set six years after the events of the last movie, the plot finds Jack and Lena Deth’s (Tim Thomerson and Hunt) domestic bliss ruined by the arrival of a new Trancers invasion — spearheaded by the dastardly Dr. Wardo (Richard Lynch), brother of Trancers 1 baddie Whistler — and Jack’s wife from his original timeline, Alice (Meg Ward).

Band referring to Trancers as his baby renders the slapdash Trancers II all the more upsetting. The props and production design are horrifically cheap; there’s a lot of awkward staging; and there are a significant number of technical flubs and continuity errors that betray a slovenly ‘that’ll do’ attitude. The film’s dialogue is clunky and mired in dense exposition, and its plotting is contrived and convoluted. Thankfully, Band and Canson unleash several clever moments to counteract the slop, such as the ‘two wives’ business and a funny scene wherein Alice tries to convince a psych ward orderly she’s not crazy by detailing her genuine backstory – which obviously makes her sound very crazy indeed. As an aside, the orderly character, Rabbit, and the actor playing him, Sonny Carl Davis, would go on to feature throughout Band’s enduring Evil Bong saga.

Cast-wise, Thomerson, Hunt, and fellow Trancers holdovers Art LaFleur, Telma Hopkins and Biff Manard are fantastic – though Jeffrey Combs, Martine Beswick, and the spectacularly creepy Lynch do the heavy lifting, elevating the largely ho-hum material with their villainous vamping. Ward – whose Full Moon credentials extend to Crash and Burn and Arcade (1994) – is disgracefully wooden (she’d grow into the role come Trancers III (1992)), and Barbara Crampton briefly appears as a talk show host.

A la Crash and Burn and Puppet Master II (1990), David DeCoteau and John Schouweiler serve as producers.

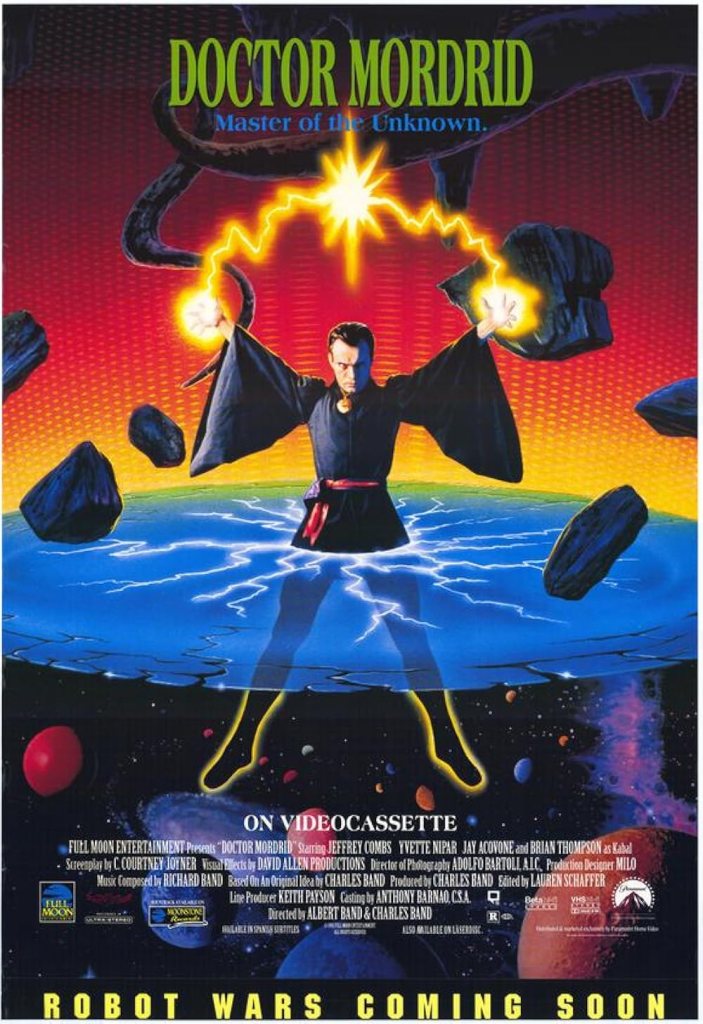

DOCTOR MORDRID (1992)

Band is synonymous with puppets, dolls and mini-monsters, but stories about feuds and sorcery are almost as common, especially within his directorial resume. Alongside Meridian, Doctor Mordrid – which Band co-directed with his father, Albert (I Bury the Living (1958), Ghoulies II) – is his definitive tale of war and wizards.

A delight, this gloriously pulpy offering concerns the eponymous hero (Jeffrey Combs) trying to prevent the gates of hell being opened by the evil Kabal (Brian Thompson – a wickedly imposing performance). Snappily scripted by C. Courtney Joyner (Prison (1987), Puppet Master III: Toulon’s Revenge (1991)), the junior and senior Band relate the story at pace. The sets by production designer Milo – his first of several standout Full Moon assignments – are excellent; David Allen’s stop motion effects are joyous; and Adolfo Bartoli’s photography is spiked with a splash panel energy wholly befitting of Doctor Mordrid’s comic book roots.

Dating back to the Empire days, the project began life as ‘Doctor Mortalis’ and was one of two prospective collaborations between Band and acclaimed comic book artist Jack Kirby (the other, ‘Mindmasters’, became Mandroid (1993)). Of course, as the Band faithful know, that was really a smokescreen to do an unofficial adaptation of the filmmaker’s favourite Marvel saga, Doctor Strange; something that’s become the driving force of discourse around Doctor Mordrid over the last few years. And that’s unfair. A rip-off it might be, but Doctor Mordrid has plenty of charm and muscle of its own to warrant evolving from amusing comic book movie footnote to canonised Full Moon classic.

Full Moon’s benefactor, Paramount, thought highly of the film and commissioned a pair of sequels that, like Subspecies II (1993) and III (1994) and Puppet Master 4 (1994) and 5 (1995), were going to be shot in tandem. Sadly, development of ‘Doctor Mordrid 2: Crystal Hell’ and ‘Doctor Mordrid 3: Shadow Queen’ sank during Full Moon and Paramount’s divorce.

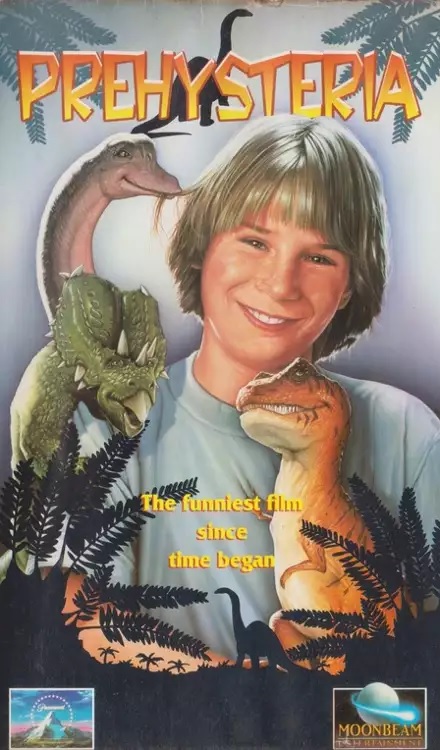

PREHYSTERIA! (1993)

Produced at the peak of Band’s union with Paramount, when the prolific B-peddler was the toast of their home video department, Prehysteria! represents the debut of Full Moon’s family friendly subdivision, Moonbeam Entertainment. Designed to ride the wave of dino-fever instigated by Jurassic Park (1993), Prehysteria! was a big, big, BIG hit on tape, leading to a pair of equally enjoyable sequels.

While occasionally sullied with the same issue as many a DTV kids’ flick, whereupon actual comedy is confused with how loudly the cast shout their lines (looking at you, Stephen Lee), Prehysteria! is lovely. At its core are a wealth of committed performances and cute – albeit rubbery – dinosaur effects by Mark Rappaport (which, naturally, are enhanced by Band perennial David Allen’s nifty stop motion). Plot sees a boy and his sister happening across a batch of eggs that, when hatched, unleash a gaggle of mischievous miniature dinosaurs.

Another father and son venture, the Bands’ light and airy co-direction is as artistically harmonious here as it is on Doctor Mordrid. Moreover, their collaboration dovetails with Prehysteria!’s theme of family and unity, adding a dollop of (admittedly unintentional) self-reflexivity that’s as cool for B-movie savvy adults as the creature-based tomfoolery is for the youngsters.

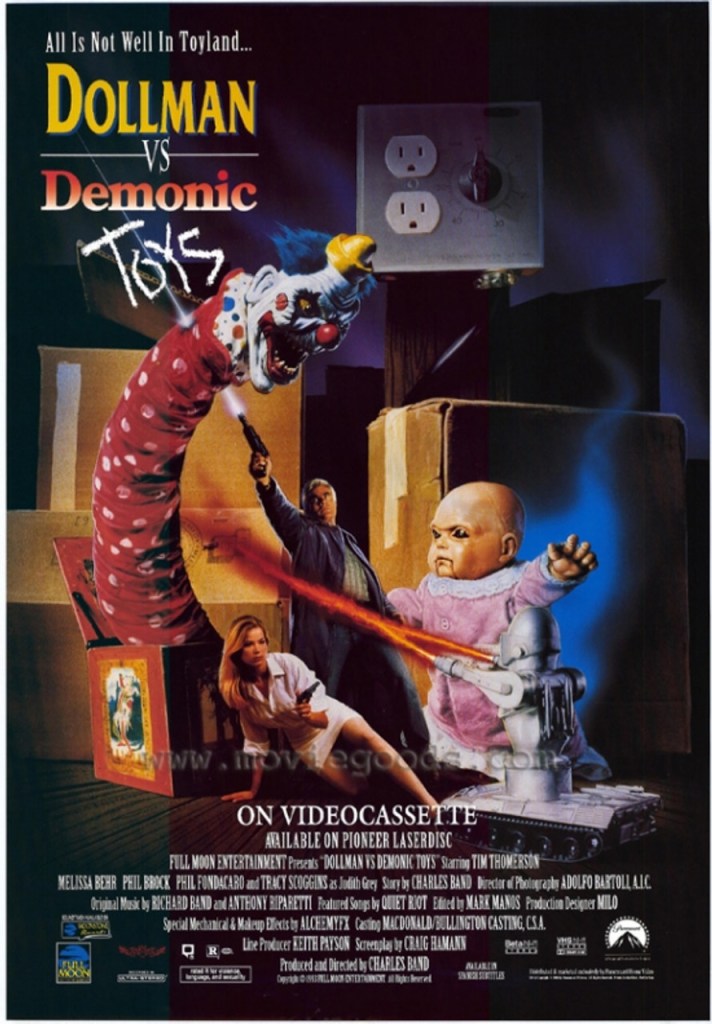

DOLLMAN VS DEMONIC TOYS (1993)

Though flawed, Dollman (1991), Demonic Toys (1992) and the underappreciated Bad Channels (1992) shouldn’t be tainted with this sorry fiasco. With the diminutive Brick Bardo already cameoing at the end of the latter, the Ronseal-like Dollman vs Demonic Toys — or, as it’s titled on screen, ‘Dollman vs The Demonic Toys’ — was meant to herald several universe-building Full Moon crossovers. However, when Paramount surveyed the finished product they were aghast, leading to the plan being pulled. Worse is that between Dollman vs Demonic Toys and budget discrepancies on the aforementioned Bad Channels and the incoming Lurking Fear (1994), the major’s new management suddenly wanted to open Band’s books to find out where, exactly, their money was going — which, in turn, is what caused the entire Full Moon/Paramount split in the first place.

At the risk of sounding sniffy, it’s easy to see why Paramount started vetting Band’s confections. Padded by shedloads of footage cribbed from its vastly — VASTLY — superior predecessors, Dollman vs Demonic Toys is excruciatingly cheap and possesses all the style of a SunLife insurance advert. It’s also insanely boring, even at a paltry sixty-four minutes. I suppose you could argue that Band’s meandering direction predates the hangout quality of his later Evil Bong films. I won’t, though, because they exhibit a modicum of goofy whimsy; a sense Band is at least attempting to entertain. Dollman vs Demonic Toys, on the other hand, emanates an unpleasant air of smugness. It’s as if the producer/helmer is laughing at us for giving it a go.

The by proxy embarrassment of seeing Dollman’s Tim Thomerson, Demonic Toys’ Tracy Scoggins, Bad Channels’ Melissa Behr, and the always welcome Band perennial Phil Fondacaro trying to bejewel such a ghastly turd with their enthusiastic mugging is painful. It’s like watching a bad best man speech. What positives the film has are largely incidental and due to the skills of the technicians involved: the oversized props used to sell Thomerson and Behr’s height deficiency elicit a chuckle, and the Demonic Toy FX — by Mike Deak, who’d crewed with John Carl Buechler and inhabited the were-bear suit on the original Demonic Toys — are superb.

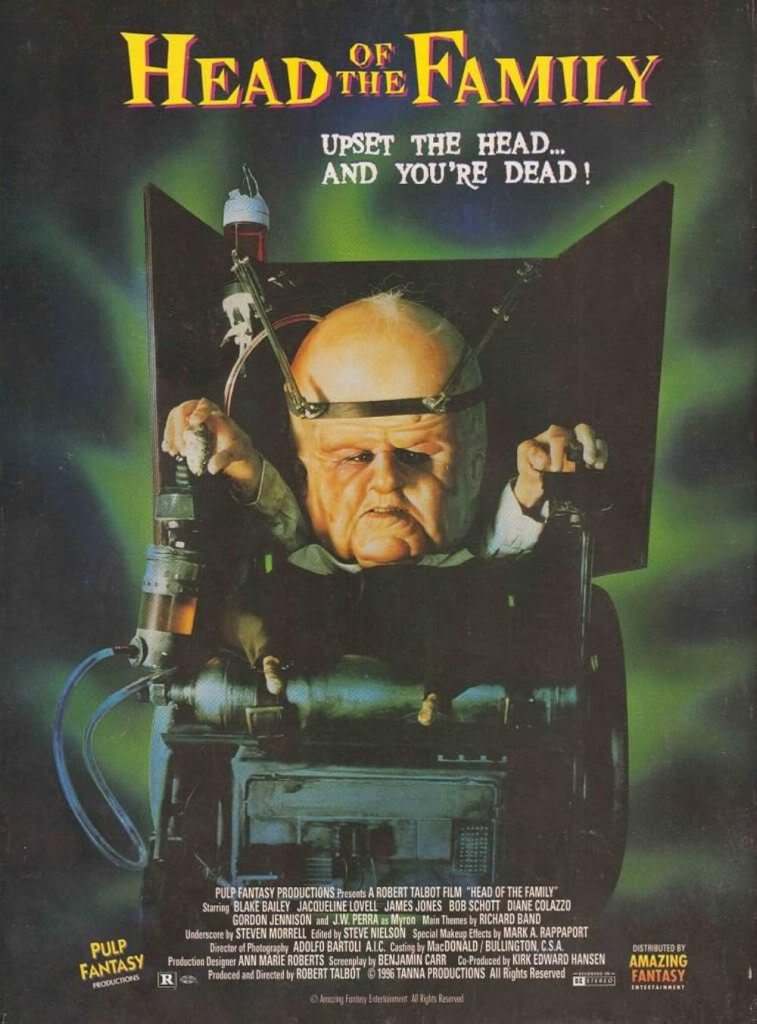

HEAD OF THE FAMILY (1996)

There are no puppets or dolls. And there’s no sorcery. However, as the title implies, Head of the Family probes another important Band theme — and the eponymous leader, the grotesquely deformed Myron Stackpool (Michael Citriniti, billed as ‘J.A. Perra’), certainly fits the mogul’s tiny terror remit.

Alongside the achingly perfect Trancers, Head of the Family is the ultimate synthesis of Band as director. The humour. The kookiness. How good a storyteller he is when sparking off a dynamite script. The technical trickery (gotta love the forced perspective stuff!). And the knowingly pulpy footing. Because although it isn’t credited, Head of the Family is, like Doctor Mordrid, a sneaky adaptation of pre-existing material. Band basically had writer Neal Marshall Stevens (as ‘Benjamin Carr’) model the Stackpool clan after characters in Jack Kirby’s Head of the Family; an obscure eight page yarn published in ‘50s comic book Black Magic.

A lively southern gothic, Head of the Family bubbles with surreal silliness, barbed dialogue, and plenty of T&A, to the point you can almost call it softcore (Jacqueline Lovell – hot damn!). But beneath the bawdy and ghoulish veneer is a surprisingly wholesome centre. Head of the Family is a film about kinship and how families come together in a crisis.

As with Prehysteria!, there’s a self-reflexivity to it. Those who’ve worked with Band often refer to the jovial family atmosphere he promotes behind the scenes. To that end, the bubble-domed Myron can be seen as a Band caricature; the mastermind controlling it all. The plot’s blend of blackmail and deception even appears to echo and allude to aspects of Empire’s crumbling and Full Moon’s split with Paramount (Head of the Family was produced in the months between the shingle’s Paramount goodbye and their Kushner-Locke hello). The most compelling read, though, is Band being mirrored in the part of Lance (Blake Adams): an ambitious, grey-shaded ‘hero’ wanting to do the right thing, but guilty of rash decisions and prone to slippery practices.

Band took the pseudonym ‘Robert Talbot’ on the finished film. I’ve always wondered if it’s because he initially felt too exposed by what’s on screen. It is – seriously – very personal.

Today he’s vocally proud of Head of the Family.

Rightly so.

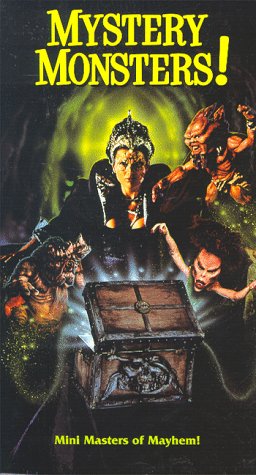

MYSTERY MONSTERS (1997)

A suitably weird hybrid of two of the weirdest DTV trends: postmodern ‘behind the scenes’ exposés about a film or TV show (cf. Fred Olen Ray’s Bad Girls From Mars (1990), Jag Mundhra’s L.A. Goddess (1993)), and kids’ movies preoccupied with ludicrously grown-up topics such as land deals, property disputes, and dodgy business dealings.

It’s tough to imagine the target demographic — you know, children — being overly engaged with Mystery Monsters. Sure, it’s bright and colourful, and its heroes are moppets. However, Neal Marshall Stevens’ script is perversely obsessed with the minutiae of financial chicanery, and the film’s creature carnage is closer to the raucous, snotty tone of Ghoulies than it is to Prehysteria! or Dragonworld (1994). Then again, maybe that’s the joke. Mounted as the start of Band’s Pulsepounders! label — a range devoted to ‘edgier’ family fodder — Mystery Monsters feels like an acknowledgement; a tip of the hat to the fact that, regardless of the proper child-friendly Full Moon fare pumped out via Moonbeam, it was the grottier, nastier stuff a la Puppet Master and Subspecies the ankle-biters were hounding their parents to rent.

Once you’re hip to it, Mystery Monsters is a minor blast, unspooling as if it were a Charles Band best of. There are winks and nods aplenty. The uninitiated will be lost but sod ‘em. The titular mini-beasts (by Mark Rappaport) are good cheesy fun; Head of the Family’s Michael Citriniti (as ‘J.W. Perra’) gets juicy multiple roles (as a TV exec and the voices of two of the beasties); and Trancers’ Biff Manard (as ‘Michael Dennis’) submits an uproarious supporting turn as a curmudgeonly presenter.

Credited to ‘Robert Talbot’ and also known as ‘Goobers!’.

HIDEOUS! (1997)

Michael Citriniti and Full Moon’s resident mid-’90s ultra-babe, Jacqueline Lovell, stole Head of the Family thanks to their plucky performances (and, in the case of the breathtaking Lovell, her willingness to get her kit off every other scene). Thus, pairing them for Hideous! must have been a no brainer. Here, though, the dynamic duo are joined by a plethora of A-grade hams – Tracie May-Wagner, Rhonda Griffin, Jerry O’Donnell, and Mel Johnson Jr. – all of whom attack the film’s sassy script with gusto.

Another from the pen of Neal Marshall Stevens (aka ‘Benjamin Carr’), the Full Moon staple has quite the ear for wordplay and verbal jousting – so much so that Hideous!’s machine gun patter becomes a little wearying. Indeed, there are a few moments where Band’s direction slackens because of it, leaving Hideous! feeling slightly stagey and stilted. Only very slightly, mind. To be clear:

Hideous! is a hoot.

Potentially set in the same world as Band and Stevens’ previous Ghoulies riff, Mystery Monsters (O’Donnell’s cynical gumshoe repeatedly refers to Hideous!’s creature contingent as ‘goobers’), plot sees Citriniti’s flamboyant Dr. Lorca and Johnson Jr.’s eccentric businessman, Napoleon Lazar, feuding over who has the best collection of – drum roll – miniature medical oddities. Events crescendo within the opulent confines of the former’s supervillain-esque castle (the film was shot at Full Moon’s studio in Romania), whereupon his supernaturally-charged specimens get loose and cause merry hell. Slickly made and lensed with impishly macabre flair, Band has a ball mucking around with old dark house conventions and Trancers-style noir tropes, and Mark Rappaport’s pint-sized beasties exude the requisite comic book élan. The film works nicely coupled with Band’s later opus, Dr. Moreau’s House of Pain (2004).

Citriniti reprised Lorca in Demonic Toys 2: Personal Demons (2010) and Full Moon’s short-lived TV show, Ravenwolf Towers (2014). Johnson Jr. went on to co-found Full Moon’s equally short-lived urban subdivision, Big City Pictures (née Alchemy).

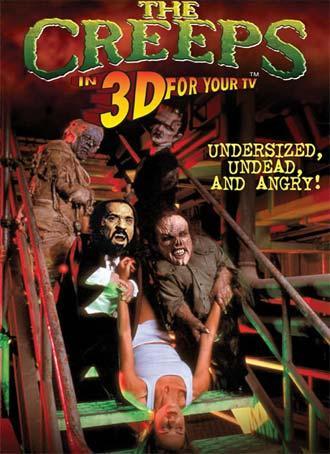

THE CREEPS (1997)

Band’s third – and best – stab at 3D after a fifteen year sabbatical from the form.

Elegantly lensed by Full Moon stalwart Adolfo Bartoli, The Creeps oozes a playfully macabre atmosphere and every shot feels as though you’re there in the thick of it thanks to the magnificent staging and production design. Typical, then, that the vast majority of folk won’t have experienced the film the way Band intended until it was issued on 3D DVD in 2004 – if, of course, they bothered to pick up the disc…

Happily, as the restored version that’s been kicking around on Blu-ray and Full Moon’s various streaming outlets since the mid-2010s proves, The Creeps works without it. Like Metalstorm, thrusting objects at the camera is (mostly) eschewed in favour of immersive storytelling; of sucking us into The Creeps’ wonderfully weird twilight world of books, movies, and monsters. It’s all the more impressive that it’s done with three sets and a smoke machine – a trick presumably influenced by Band’s ongoing collaboration with David DeCoteau, who was churning out a string of similarly small but mighty programmers for the maven (cf. Shrieker (1998), Talisman (1998), Curse of the Puppet Master (1998)).

Speaking of which, ‘small but mighty’ is the essence of The Creeps’ plot. Band’s affectionate tribute to Universal Monsters, the film concerns the obligatory mad quack (Bill Moynihan) conjuring – here it comes – miniature iterations of Dracula (Phil Fondacaro), Frankenstein’s Monster (Thomas Wellington), The Mummy (Joe Smith), and The Wolf Man (Jon Simanton) via his “Archetype Inducer” device. The film’s ensemble cast – rounded out by Rhonda Griffin, Justin Lauer, and Kristin Norton – are unanimously brilliant. Fondacaro in particular relishes the chance to assume such an iconic role. As the Band fav says in The Creeps’ VideoZone, “Little people never get to do these parts”. What makes Fondacaro’s sentiment even better is that Band never, well, belittles the horror. Despite their size, the titular creepers are still presented as formidable, fright-inducing threats.

Elsewhere, Gabe Bartalos’ make-up effects are likewise rapturous and reverential (he, too, seems elated to be noodling in the Universal sandbox). And, while it ties itself in a post Scream (1996), post Tarantino pop culture knot on occasion, Neal Marshall Stevens’ script houses several quality in-jokes. The funniest? Michael Citriniti — ‘J.W. Perra’ — cropping up as a snooty video store customer requesting copies of Head of the Family and Hideous! alongside Portrait of a Lady (1996) and The Bridges of Madison County (1995).

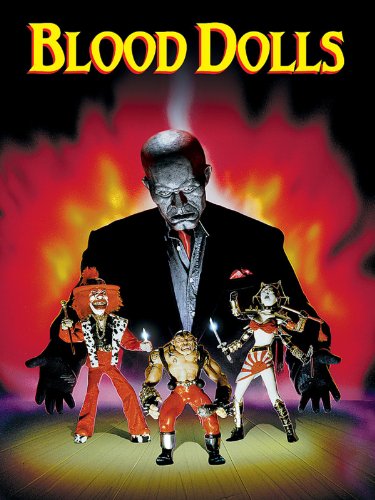

BLOOD DOLLS (1999)

A rock n’ roll fever dream – music, William Castle kitsch, Bond villain shtick, and Band’s patented killer puppets. Although a couple of moments strive a little too hard for quirky cool, Blood Dolls is sensational. Directorially the film’s up there with Trancers, Meridian, and Head of the Family. Zippily paced, it teems with brain-searing images that run the gamut from sexy and silly, to perverse and disturbing.

Touted as a bona fide auteur vehicle (many home video copies are prefixed by Band’s name above the title), Blood Dolls credits Band’s alias, ‘Robert Talbot’, as its writer. The basic elements – revenge, feuding, mad science – will be Band’s invention, per his concept/poster technique, but Neal Marshall Stevens’ fingerprints are all over the quotable dialogue and outrageous character tics. A satire on the wants and needs of the rich and powerful, Blood Dolls tells the story of megalomaniacal pinhead Virgil Travis (Kristopher Logan, as ‘Jack Maturin’) and the campaign of terror he wages against the greedy couples (Nicholas Worth and Jodie Fisher, and Warren Draper and much missed ‘00s Full Moon staple Debra Mayer) responsible for tanking his company. Assisting Travis are the eponymous dolls (built from designs by FX wiz Mark Williams — some of his final work prior to his untimely passing); his bad-tempered butler (Phil Fondacaro) and brooding clown henchman, the unforgettable Mr. Mascaro (William Paul Burns); and the all-girl rock band he’s got caged up in his mansion for his own musical amusement (their second cut, ‘Pain’, is a bop). Wild for sure – and further intrigue is generated by the film crossing over with other Full Moon properties. Mr. Mascaro is Demonic Toys’ Jack Attack in human form, and Travis is the test tube son of Head of the Family’s Myron Stackpool, afflictions reversed. Travis doesn’t mention Myron, but he passes comment about his mother, Eugenie, who, if you’re in tune with denser Band shenanigans, was the wife-to-be in the unmade Bride of the Head of the Family.

Assembled in conjunction with music magnate Miles Copeland, Band had grand plans for Blood Dolls. The group – christened The Blood Dolls and marketed as “The Anti Spice Girls” – were going to tour and record an album, while both the film’s making and The Blood Dolls’ nationwide takeover were to be chronicled by Penelope Spheeris in a documentary called ‘Hollyweird’. It’ll stun you to hear this, but the tour, album and doc hit the skids. However, a five minute portion of the latter (misspelt ‘Hollywierd’) can be viewed as an extra on assorted DVD releases.