Matty dissects a trendsetting serial killer biopic.

Independent producers Michael Muscal – a collaborator of horror master Brian Yuzna – and Hamish McAlpine – head of Tartan Films – were going to make a ghost film until a pair of big, poorly received studio spookshows, The Haunting (1999) and House on Haunted Hill (1999), put them off the idea. Still wanting to work together, the two fired a few more potential concepts back and forth. Nothing clicked until McAlpine fielded a meeting with a mutual acquaintance, who noticed a bust of murderer Ed Gein sitting on the mogul’s shelf. And as luck would have it, the acquaintance, screenwriter Stephen Johnston, happened to have a script about Gein and his crimes…

As the millennium approached, Gein’s worth as a pop culture commodity was at an all-time high. True crime author Harold Schecter’s essential 1989 book on the graverobber and suspected serial killer, Deviant, was republished, and the American press were frequently reporting on the folk-hero status Gein had attained online; a morbid adoration that peaked with the theft of the ghoul’s grave marker, and mounds of dirt from his place of rest being sold on eBay. Movie-wise, mid-‘90s serial killer thrillers a la Se7en (1995) and Copycat (1996) were continuing to fare well on video and cable, and several films explicitly influenced by various aspects of Gein were in the spotlight for a multitude of reasons.

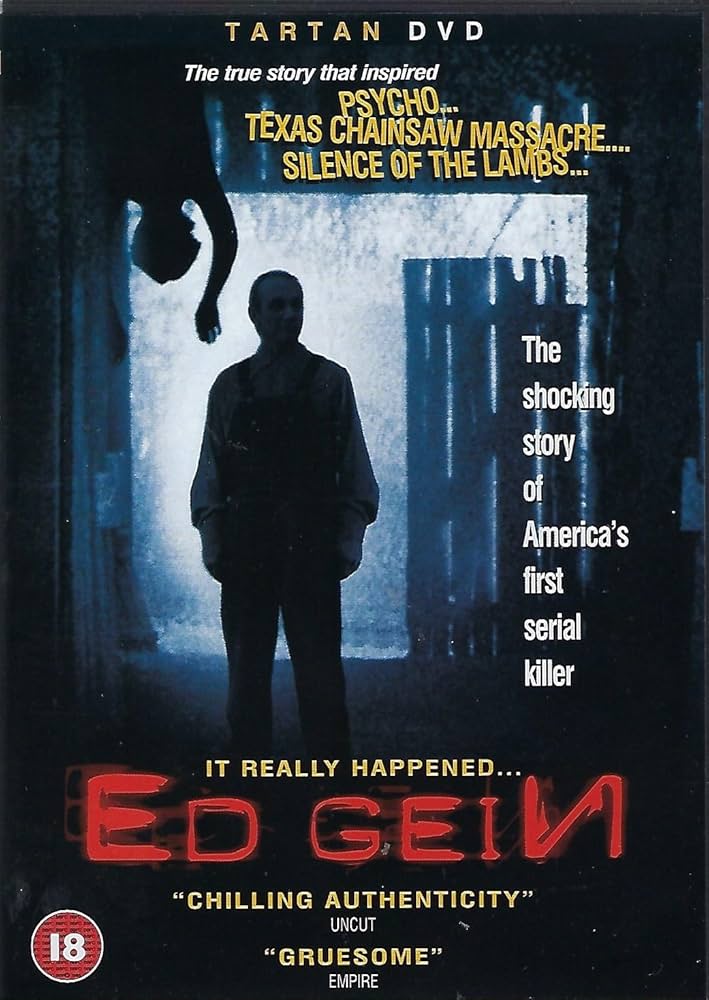

Psycho (1960) – the first film inspired by Gein’s nefarious activities – was remade.

The Silence of the Lambs (1991) – the most decorated – was getting a sequel.

And The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) – the most infamous – was celebrating its twenty-fifth anniversary with a re-release.

When Muscal, McAlpine, and Johnston’s ED GEIN (2000) entered production, its cinematic lineage was a central topic of conversation. A showman at heart, McAlpine was quick to talk up their version, telling Fangoria “we’re deliberately portraying Ed as a real human being” before passing over to the film’s director, Chuck Parello.

“Anytime our film went in the direction of those other movies, I one-eighty’d away from them,” said Parello. “I haven’t seen every horror film ever made… But I’m not repeating scenes that might have been in other films.” [1]

Parello’s path to Ed Gein was nearly as unusual as its subject. Mounted as ‘In the Light of the Moon: The Ed Gein Story’, scripter Johnston lobbied to helm but was vetoed due to his inexperience. Thinking him a good prospect based on past form, McAlpine broached Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer’s (1986) John McNaughton about taking the reins. McNaughton declined but pointed him towards Parello, who’d brought in Henry’s follow-up. According to Parello, the recommendation came after McAlpine started ribbing McNaughton at Cannes. He’d clocked a poster for Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, Part 2 (1996) and believed it to be a shoddy cash-in. McNaughton scolded him. He told McAlpine to check the film out, and affirmed that Parello was actually a friend of his.

McAlpine wound up impressed.

Like Henry 2, Ed Gein benefits from Parello’s focus on character. However, Henry 2 was an ensemble piece. Ed Gein is, as its title suggests, primarily a one man show. Serving as a companion of sorts to his earlier powerhouse turn as Charles Manson in iconic ‘70s miniseries Helter Skelter (1976), Steve Railsback is a magnificent Gein. Wholly embodying the role, Railsback spent three months engulfed in research, and occupies every facet of Gein’s persona; from nice but dim neighbour and grieving mama’s boy, to disquieting oddball and, ultimately, cadaver-faffing lunatic. An air of doomed tragedy hangs over his towering performance. In Railsback’s hands, Gein has monstrous predilections but is not a monster. He’s a simple, gullible soul broken by child abuse, religious dogma, gender confusion, and – worst of all – loneliness.

Though sticking closely to Gein’s story, the film chops and changes some of the facts for dramatic effect. While Alan Ormsby and Jeff Gillen’s harrowing masterpiece, Deranged (1974), remains the strongest and queasiest Gein flick in totality (albeit with the killer renamed and his MO slightly more sexualised), Parello exhibits a similarly unflinching – if tamer – view of the case’s iconography. Dead skin masks, bone furniture – the film is sprinkled with signature Gein props and situations. Despite the sequence’s brevity, Gein’s moon dance is a disturbing and unsettling moment made freakier due to Parello’s fixation on psychological accuracy.

Paradoxically, it’s Parello’s wackier, fanciful flourishes that hinder the film. The slice o’ life lingering on certain townsfolk feels laboured, and Ed Gein dips whenever Railsback is off screen. The flashbacks involving Gein’s mother, Augusta (Railsback’s Trick or Treats (1982) co-star Carrie Snodgress), are excellent and vividly depict the domineering matriarch’s contributions to her son’s psychosis. Less convincing are the spectral visions of Augusta which Parello added during his re-write of Johnston’s script. They’re a cheap and trope-y device, and they undercut the realism Parello fosters elsewhere.

Technically robust, Ed Gein is atmospherically shot. More conventionally filmic than Henry 2, it’s nevertheless part of the same docudrama tapestry thanks to Parello’s observational and studious presentation. The period production design and costuming is excellent, especially in relation to the film’s low budget, and Parello’s Henry 2 composer, Robert McNaughton, amplifies the fracturing of Gein’s mind with an evocative score.

Lensed in November/December 1999 [2] in Topanga Canyon, California, Ed Gein was going to be shot in Gein’s home state of Wisconsin until a mixture of logistics, costs, and angry locals deterred the filmmakers. As the Wisconsin Film Commission told McAlpine, if the production went within one-hundred feet of Plainfield, where Gein lived, their safety couldn’t be guaranteed. The town had spent years trying to distance themselves, fending off dark tourists and assorted rubber-neckers.

Ed Gein premiered in London at the inaugural FrightFest in August 2000, and played Sitges Film Festival, Spain the following October where it won Best Film and Railsback won Best Actor. Upon its Sitges bow, Parello struck a development deal with Muscal’s old pal, Brian Yuzna, and his recently minted Spanish shingle, Fantastic Factory. Off the back of it, Parello almost wrote and directed the film that became Romasanta: The Werewolf Hunt (2004) under Paco Plaza’s stewardship. As with Henry 2 and Ed Gein, Romasanta was based on a real-life murder case.

Ed Gein opened theatrically in a single cinema in Los Angeles on 4th May 2001. It hit video in the U.S via First Look/DEJ and in the U.K. via High Fliers – both in conjunction with McAlpine’s Tartan – on 24th June ‘01 and 29th November ‘01 respectively. Given the publicity surrounding the film, Ed Gein rented extremely well and amassed a tidy profit, leading Muscal and McAlpine to fast track another serial killer biopic, Ted Bundy (2002) (which, incidentally, was scheduled to be directed by Parello until Freeway’s (1996) Matthew Bright stepped in).

And just like that, one of DTV horror’s strangest subgenres was up and running…

[1] Ed Gein Digs Up the Past by Anthony C. Ferrante, Fangoria #204.

[2] At the time of the film’s making, another Gein biopic was in development at Robert E. Baruc’s Unapix. Incredibly, the project — spearheaded by Martin Kunert and Eric Manes (Campfire Tales (1997), MTV’s Fear) — began life as a prospective Texas Chain Saw Massacre sequel called ‘TX25’. When it contorted to its fact-based form, James Woods and Steve Buscemi were considered for Gein.