This USA Network TV movie dates back to the late ’70s, when director Robert Harmon and his then girlfriend, Beth Tate, hatched a plan to get noticed by Hollywood. Dave chats to Beth to find out more…

After attending film school at Boston University, Robert Harmon began to take on a few jobs as a set stills photographer. Work came his way on early Charles Band productions Adult Fairytales (1978) and The Day Time Ended (1979) – but Harmon’s goal was to move into directing. Sharing this ambition during the twilight years of the ‘70s was his then girlfriend, Beth Tate.

“I met Robert back in 1978 while visiting a film set – a low budget Irwin Yablans/Charlie Band horror picture called Tourist Trap (1979). Both of us were new arrivals after graduating from film school, and we hit it off immediately and began dating and dreaming. My role models at the time were Debra Hill and John Carpenter. Harmon was more into the epic style of David Lean. We were a quirky mix!”

Together Tate and Harmon decided to make a short to demonstrate – as the latter so eloquently put it – that they could be trusted with huge sums of someone else’s money. Starring Charles Napier as a serial killer cop, China Lake swelled into a three year journey that cost the couple every penny they had. Shot in Joshua Tree on short ends over eleven days in 1981, the short didn’t get finished until 1983. Harmon was convinced that they’d only have one chance to prove themselves, hence the determination to take as long as necessary.

It was worth it, though, at least for Harmon: by late 1984, he was knee-deep in preproduction on The Hitcher (1986) – arguably be one of the most iconic films of the decade. For Tate, however, the doors opened by China Lake are darkened by regret.

“The reaction to it was immediate and frankly overwhelming,” she sighs. “That short propelled us into the highest levels of the Hollywood A system. It was an interesting time but not necessarily a happy one: what had been a tight knit group of friends was torn apart by the Hollywood machine. The only person who managed to come out of it unscathed was our third partner, editor Zach Staenberg, who years later won an Academy Award for The Matrix (1999).”

“I ended up with development deals, first with David Giler at Columbia and then with Stuart Cornfeld at Fox. What I learned from that experience was, at the studio level, since very few pictures are given the green light, most of what that world is about is dealmaking and manoeuvring, and little to do with actual filmmaking. At first it was hard to accept that my dreams weren’t going to come true because I wasn’t going to play those games. But this did lead me to the discovery that it doesn’t matter what you create, as long as you create.”

“Years ago I was given advice that the studio system should be avoided until one is firmly established. Sound advice. We were just too young to heed it.”

While both Harmon and Tate were being wooed by Tinseltown, China Lake was still lingering in the minds of several executives, notably those at the USA Network who were toying with the intention of expanding it into a feature. Alas, there would be no participation from either of the short’s progenitors.

“Robert just wasn’t interested in a TV project as he was off doing features”, recalls Tate. “And for me – well, it was amazing I got what I did, which was an associate producer namecheck. I wasn’t a WGA writer, so despite trying for a screen credit I simply had no back-up.”

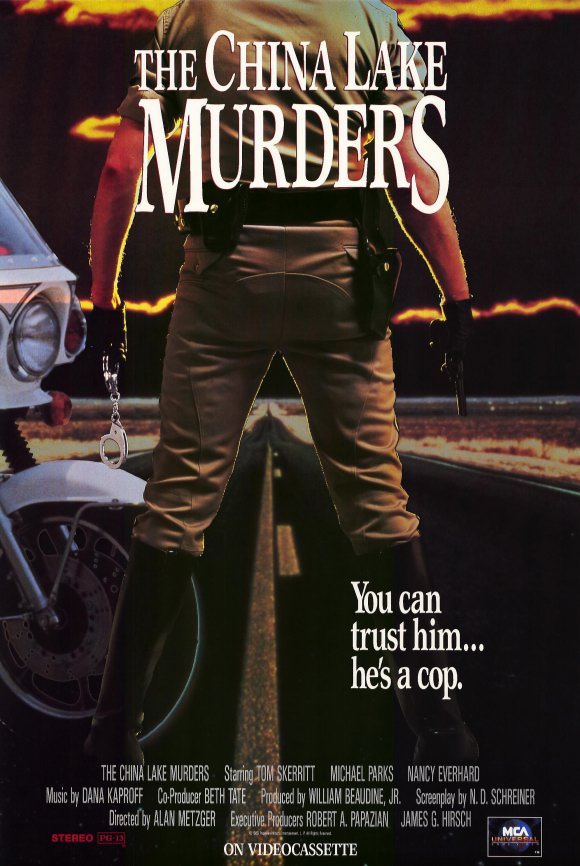

In their place, the USA Network hired Alan Metzger, fresh from a lengthy run on The Equalizer, to direct and Nevin Schreiner to script. Nevertheless, THE CHINA LAKE MURDERS (1990) utilises pretty much every dramatic aspect of Harmon and Tate’s original, occasionally verbatim, which makes the absence of a hat tip particularly frustrating. Taking Napier’s place as the nefarious Officer Donnelly is Michael Parks: a move that transforms the film into essential television. Indeed, it’s a role like Donnelly that truly underlines what a special actor Parks was. As his nemesis – and in a plot strand Schreiner developed, presumably in order to hit feature length – is the brilliant Tom Skerritt as Sheriff Sam Brodie. The antithesis of Donnelly, Brodie is very much a morality-driven law enforcer. Scarred by a recent separation, he’s a subdued character whose personal demons are perilously close to the surface.

Filmed – and stop me if you’ve heard this before – in Joshua Tree over the course of eleven days, The China Lake Murders negotiated a four month turnaround (it was shot in September 1989) and aired on 31st January 1990. Although the telepic misses the intensity of its hugely effective predecessor, it warrants praise for a number of aspects beyond Parks and Skerritt’s powerful strutting. Dana Kaproff’s haunting score doesn’t quite have the same swirl as David Gibney’s, but it’s an impressive piece of work. Similarly, Geoffrey Schaaf’s sun-kissed photography might not match Harmon’s own lensmanship, but The China Lake Murders is still a beautiful picture to look at, and Schaaf has no compunction about making the desert the main attraction.

“It was just a watered down rendition for a mass audience,” says Tate when asked about The China Lake Murders. Elements of that statement are correct, yes, but that’s largely due to how spectacular China Lake was. Irrespective of who made it, a remake or expansion was destined to pale in comparison.

The fact The China Lake Murders is such an impressive attempt at adapting perfection has to be applauded.