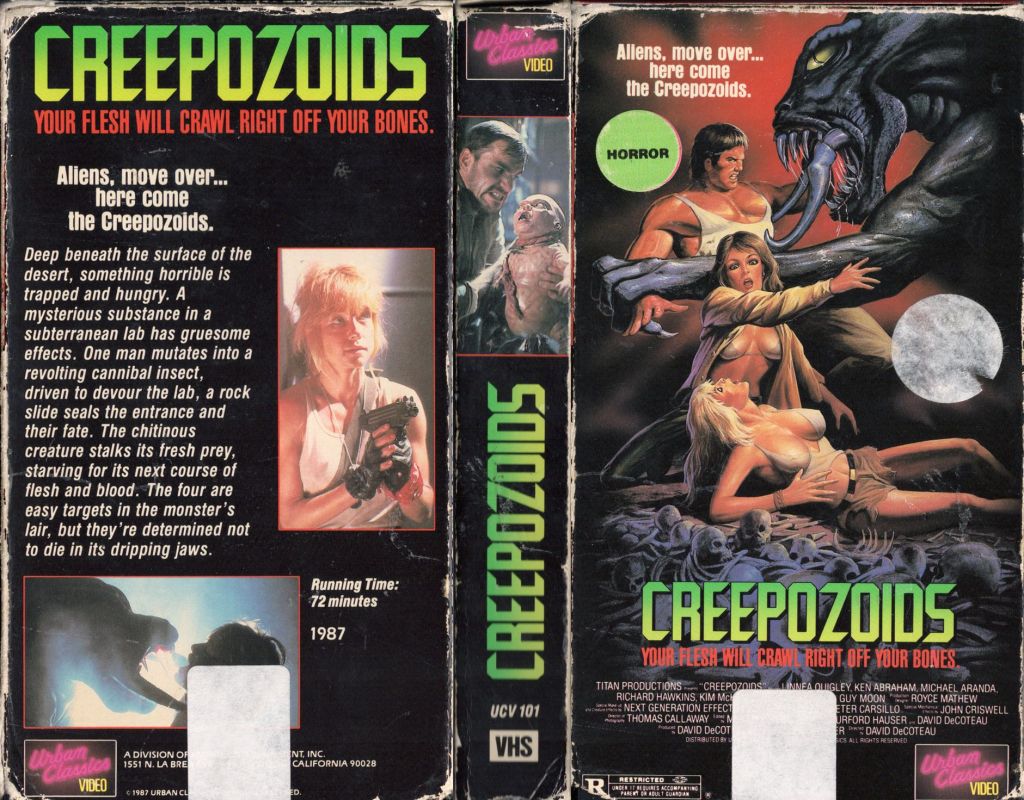

From the vault: a revised version of Matty and Dave’s look at David DeCoteau’s cheap n’ cheerful sci-shocker, as originally published in 88 Films’ now out-of-print Blu-ray. Featuring interviews with screenwriter Dave Eisenstark and production designer Royce Mathew!

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.

At least that’s what Sir. Ridley Scott must tell himself, such is the impact of the Academy Award-nominated maestro’s 1979 classic, Alien, on horror filmmaking. In fact, George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) and John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) aside, you’d be hard pressed to find another film that’s been aped more, particularly at the lower-budgeted end of the terror spectrum. Perfect when you think about it, what with Scott’s intergalactic scare-fest being so deeply indebted to the sci-fi horror programmers of yore.

There’s been plenty written about Alien’s pulpy, B-movie inspirations. From The Thing From Another World (1951) and It! The Terror From Beyond Space (1958), to Mario Bava’s opulent cosmo-gothic Planet of the Vampires (1965), Scott’s name-checked influences are a stew of kitsch and cult cool. So, for the commercial and critical success of Alien to trickle back down and reinvigorate the type of picture that spawned it is as delicious as it is harmonious.

Poetry almost: the cannibal, cannibalised by its own offspring.

Of course, conventionally speaking, few of Alien‘s knock-offs manage to replicate Scott’s sense of scope or elegance – even the excellent ones like Inseminoid (1981), Galaxy of Terror (1981), and Creature (1985). Hell, the bulk of ’em aren’t even set in space, as those who’ve beer n’ pizza’d to Contamination (1980), Scared to Death (1980), and The Deadly Spawn (1983) can attest.

But that’s beside the point.

Because what all of the above lack in finesse and, in certain cases, ambition, they atone for in entertainment and spectacle.

They’re wacky and they’re lurid, and they’re each as enjoyable – as essential – as Alien because of it.

Just look at CREEPOZOIDS (1987).

“Oh, yeah, we were pretty blatant! Alien was a big deal so Creepozoids was definitely geared towards an audience wanting another film like that,” states Creepozoids’ writer, Dave Eisenstark. “Inspiration might be stretching it a bit, and I don’t recall mention of any other specific films, but I think the original Thing and The Blob (1958) factored in there somewhat, and I was always a fan of Fiend Without a Face (1958). For my part, watching all those movies as a kid really paid off.”

Chas and Dave and Dave Too

Bankrolled by genre maven Charles Band and directed by the prolific David DeCoteau, Creepozoids was slung together in the halcyon days of Band’s iconic ’80s stable, Empire Pictures. It was the first production in Empire’s short-lived Urban Classics subdivision and the film that resulted in DeCoteau being offered a ten-picture deal with the studio, after Band was suitably impressed with Creepozoids‘ dailies. With the producer having previously stumped up the completion funds for DeCoteau’s debut proper, Dreamaniac (1986) [1], the post-Creepozoids agreement between Empire and DeCoteau’s Cinema Home Video made the pages of Variety in August 1987, and would lead to the director becoming Band’s most trusted lieutenant for well over the next decade, overseeing the spritely Sorority Babes in the Slimeball Bowl-O-Rama (1988) and Dr. Alien (1988) for Empire, and a slew of goodies for Band’s subsequent Full Moon Entertainment.

Conceived as ‘Mutant Spawn 2000’, Creepozoids began as a screenplay by Will Schmitz (incidentally, another Schmitz script, ‘One Woman Death Machine’, would also form the basis of DeCoteau’s ace Death Wish (1974) riff, Lady Avenger (1988)). However, ‘Mutant Spawn 2000’ strayed too far from the stringent Alien formula DeCoteau wanted to stick to. Scrapping Schmitz’s draft, Eisenstark was tasked with the assignment, rechristened Creepozoids.

“I was introduced to David DeCoteau by our mutual friend Jackie Snider,” explains Eisenstark, who wrote the film under the pen name ‘Burford Hauser’. “I grew up loving movies and I always planned on writing. I wrote a couple of films with Jackie, including ‘Survive: 2499’ which we sold but never got produced. I think Jackie gave David one of my horror scripts. David told me the Creepozoids story in about thirty minutes in his office and I took notes. He covered it completely, but I supplied all the specific action and dialogue; you know, the ‘real writing’ stuff! I was given a seven-day deadline but I normally write pretty quickly anyway so it wasn’t a problem.”

Weaving in a dash of the post-apocalyptic (a symptom of the glorious Mad Max (1979) hangover of the ’80s, with George Miller’s rollicking Ozploiter arguably the next picture on the NOTLD/Halloween/Alien scale of influence), Creepozoids finds a group of army deserters fleeing across an America ravaged by a nuclear exchange. Per a scene-setting intertitle – which places Creepozoids in the now not-quite-as-futuristic-sounding 1998 – what’s left of Earth is apparently a “blackened husk” plagued by “mutant nomads”; snappy ideas the perpetually frugal DeCoteau limits to a trudge under Los Angeles’ famous Sixth Street Viaduct and some throwaway exposition in the final product.

DeCoteau does, though, make good on the intertitle’s threat of “deadly acid rain”. Thanks to the magic of some scratchy storm stock footage, it’s the plot device that kicks the pacey, monster-on-the-loose shenanigans teased in Creepozoids‘ prologue into gear. Fleeing a downpour, the deserters seek refuge in an abandoned research facility, believing it a decent hideout from any shady government folk who might want to haul their sorry backsides back to the frontline. Alas, as with the husk and mutants before it, Eisenstark’s stab at expanding Creepozoids‘ universe with another bold speculative notion is hampered by DeCoteau’s paltry $70,000 budget, and the director’s refusal to move beyond the rudimentary narrative he helped conceptualise. And that’s a damn shame: whenever DeCoteau really sinks his teeth into the nuances of a screenplay, it often results in his finest work, as his lavish sequel Puppet Master III: Toulon’s Revenge (1991), taut small town thriller Skeletons (1997), and bawdy creature feature Leeches! (2003) would go on to show. Indeed, had DeCoteau embellished Eisenstark’s intriguing Cold War subtext, Creepozoids could have been as potent a piece of satirical science-fiction as Empire’s beloved swansong, Stuart Gordon’s sweeping 1989 epic Robot Jox.

But to lambast DeCoteau for not building upon Eisenstark’s thinly veiled political swipe is, again, beside the point.

Creepozoids isn’t meant to be commentary.

Always quick to dodge suggestions of auteurism, DeCoteau is a self-proclaimed journeyman. He’s a staunch propagator of simply being a slave to the market; to the demands of what’ll fly off video store shelves, be they physical or digital. And while those hip to the accomplished filmmaker’s homoerotic quickies under his Rapid Heart banner (the standouts being Ancient Evil: Scream of the Mummy (2000), Beastly Boyz (2006), and the Brotherhood sextet (2001-2009)) know that’s absolutely not the case, rammed as they are with overlapping themes and images, Creepozoids can be wheeled out as DeCoteau’s defence should he ever be forced to quash accusations of being a genuine artiste in a court of law [2].

By and large Creepozoids is the ultimate example of filmic box-ticking.

An art-free zone.

Alien 101

Now, describing Creepozoids as an ‘art-free zone’ isn’t a slam, honest.

There are multiple shades of grey between art and craft – especially when it’s a David DeCoteau picture under the microscope.

Like Euro-sleaze guru Jess Franco, Hammer stalwart Terence Fisher, and Ridley’s dearly departed brother Tony Scott, DeCoteau’s output can be split at each pole, every other film. For every personal, art-laced endeavour a la gay rom-com Leather Jacket Love Story (1997) and the awesome Voodoo Academy (2000), there’s a mercenary technical exercise like The Wrong Roommate (2016) and The Wrong Child (2016) – a pair of efficient ‘cuckoo in the nest’ TV movies for the Lifetime channel. Although Creepozoids lacks the impassioned fluidity of a filmmaker completely in tune with his material – the mesmeric vim of DeCoteau laying his soul bare across the screen – it is a movie of stellar practical skill and audience-pleasing moxie. Particularly if said audience are after scream queen Linnea Quigley getting frisky in the shower…

“Ah, the shower scene,” chuckles Creepozoids‘ production designer, Royce Mathew. “That shower was exactly four point five gallons of water. Why? Because it was actually a large water bottle from a drinking cooler that I rigged up to a shower head. Needless to say, it was one take!”

Occurring roughly a quarter of an hour into the film’s brisk, seventy-odd minute run time, Quigley’s steamy soap-down tells you everything you need to know about Creepozoids:

You’re in exploitation country.

A metropolis of boobs, slime, and brassy bloodshed.

And as Quigley’s neophyte co-star, Ken Abraham (who’d later appear in DeCoteau’s irresistible smut-noir, Deadly Embrace (1989)) fondles the starlet’s body, you can practically hear DeCoteau’s impish shrieks of merriment. He’s holding us at the top of the rollercoaster, allowing us to see the jerks, loops, and corkscrews of the familiar – yet nonetheless exhilarating – track he’s laid out ahead.

Lensed in the former studio of Hustler photographer Suze Randall, DeCoteau ekes a wealth of claustrophobic tension from the small Washington Boulevard workspace, which is decorated with Mathew’s pleasingly grubby sci-schlock dressing.

“The design of anything is dictated by the budget,” muses Mathew. “On Creepozoids I had very little money to work with. But I loved the challenge! David wouldn’t give me a lot of time to do all the tricks that I had planned either, but he was amazed that, all by myself, I managed to put together props, sets, wardrobe, and more. I went through trash and would drive through neighbourhoods, filling my car up with junk. I was able to rent some hospital furniture props for the lab stuff, and the ‘generator’ was actually a washing machine I took apart and reassembled and painted black. I was working eighteen hours a day, seven days a week. I was first on set and last to leave. I remember I started to build the creature’s lair immediately after we wrapped the day before. I spent the whole night working on it, no sleep, and it was finished just as David and the crew came in.”

Naturally, it’s the creature – well, creatures – that are Creepozoids‘ biggest boon. Punctuating passages of expository babble about amino acids and covert biological experiments, the hulking Zelda is the monstrous centrepiece, while a giant rat and an It’s Alive (1974)-esque mutant baby provide distinguished support. Designed by Peter Carsillo and brought to life by Thomas Floutz (quite literally too; as well as fabricating the suit, Floutz was also the poor sod wearing it), Zelda is a rougher, insectile spin on H.R. Giger’s sleek xenomorph. Part beetle, part comic book throwback – National Geographic by way of Bernie Wrightson – the waggish sparkle that Creepozoids fizzes with whenever Zelda is on screen is as contagious as the weird, zombie-ish fever that the beast passes on via its pincer-powered bite.

That the lion’s share of Creepozoids‘ Zelda-fronted set pieces are pretty much cribbed from Alien wholesale is, once more, beside the point. DeCoteau even has the temerity to appropriate Scott’s dinner table staging for Creepozoids‘ ‘chestburster moment’. They’re assembled and executed with enough poverty row dynamism, DeCoteau ladling on the dry ice and garish lighting, to make them seem as sincere as any of the jolts that Alien is full of. As noted, Creepozoids‘ path might be well trodden, but the journey itself is a blast.

By the time the Cohen-tinged terror tot crawls from Zelda’s cranium during Creepozoids‘ closing stretch, teasing a sequel that sadly never happened, it’s thumpingly obvious that cherry picking from Alien was absolutely the right thing to do. Alien is the most structurally perfect film of its kind, and James Cameron’s barnstorming follow-up, Aliens (1986), is second. And had DeCoteau’s once-planned ‘Creepozoids II’ came to fruition, you can bet your bottom dollar Cameron’s adrenaline-pumping masterpiece would have been similarly – lovingly – pillaged.

The bigger, louder, gorier approach would have been the only way to guarantee we’d all watch it.

[1] Prior to Dreamaniac, the then twenty-four year old DeCoteau cut his teeth pseudonymously wielding the megaphone on several hardcore porn flicks, most notably Making it Huge (1985) for Gayracula (1983) producer Terry LeGrand.

[2] But as ardent students of DeCoteau know, if you scratch the surface, Creepozoids’ central conceit – that of someone fighting against a force much stronger than they – is a typical DeCoteauian flourish. Practically every DeCoteau picture is anchored by it.