Matty heralds an unsung classic from director Katt Shea and producer Roger Corman.

Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957), A Bucket of Blood (1959), Little Shop of Horrors (1960), and the Poe Cycle – namely, The Pit and the Pendulum (1961) and The Masque of the Red Death (1964) – are the works cited when it comes to canonically ‘classic’ Roger Corman flicks.

However, in terms of volume and sheer quality, 1990 was the greatest year in the late B-movie titan’s unprecedented career.

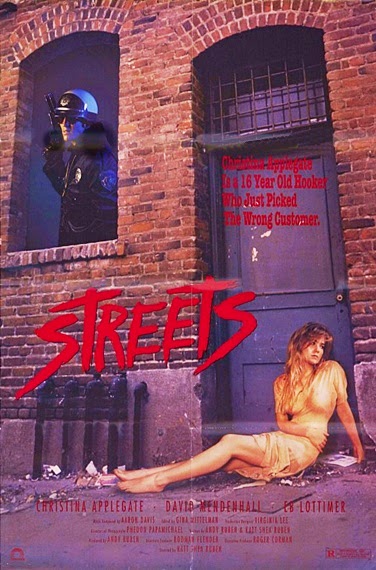

In addition to making his long-awaited return to the director’s chair with the mighty Frankenstein Unbound (1990), Corman, as producer, unleashed such barnstorming gems as Brain Dead (1990), Body Chemistry (1990), Naked Obsession (1990), and the appropriately Poe-tipping Haunting of Morella (1990). And though Body Chemistry and Naked Obsession are close, the crown jewel in Corman’s impeccable 1990 run is the picture that kickstarted it, STREETS [1].

Directed by Katt Shea and written by Shea and then-husband/creative partner Andy Ruben, Streets is the helmer’s best movie and, in many ways, a true best-of experience vis a vis themes, tone, and execution. Indeed, despite Shea’s debut, Stripped to Kill (1987), exerting more of a lasting influence on exploitation films – ditto big post-Corman assignment, Poison Ivy (1992), which New Line Cinema hired her to shepherd on the strength of Streets – this magnificent mini-epic remains her defining moment. It’s effectively the ultimate synthesis of Shea’s hallmarks and fixations. Her gritty yet dreamy aesthetic; her kinship with complicated characters; and her fascination with people in search of their purpose — or, at least, their search for temporary acceptance and connection from those in similar circumstances. Watched sequentially, after preceding Corman assignments Stripped to Kill, Dance of the Damned (1989) and Stripped to Kill II: Live Girls (1989), it’s clear Streets is the assured, fried-gold masterpiece Shea was building towards. In a particularly humorous and knowing touch, Streets’ irresistible self-confidence is accentuated by a waggish casting gimmick that sees the leads of each prior Shea joint appearing, with Stripped to Kill’s Kay Lenz and Dance of the Damned’s Starr Andreeff popping up for memorable, single-scene guest spots, and Stripped II’s hero detective, Eb Lottimer, essaying the reverse – a psychotic beat-cop – as the film’s antagonist.

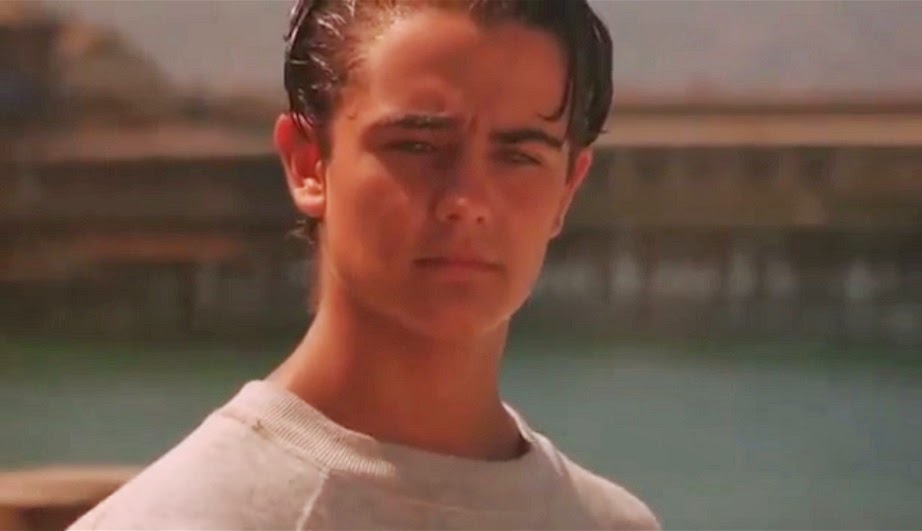

Like the bulk of Shea’s wares, Corman and otherwise, the lurid and sensational thrust of Streets’ plot – wherein Lottimer’s diabolical, prostitute-killing motorcycle officer, Lumley, pursues a trick-turning teenage-runaway (Christina Applegate, hot due to her breakout role in iconic sitcom Married… With Children) and her wannabe-rockstar love interest (David Mendenhall) – is counteracted by her fantastical approach. There’s a hazy, feverish energy to the film which only increases as it blasts along. That said, the scuzzy world in which Streets unfolds – Los Angeles’ underbelly – isn’t sanitised or softened. Where Applegate’s Dawn and her homeless friends dwell still oozes danger, despite the flutters of visual and atmospheric extravagance.

Shot in and around Venice Beach over nineteen days between July and August 1989, and opulently lensed by key Shea collaborator Phedon Papamichael (whose crew also included fellow Corman alumni/future Hollywood heavyweights Wally Pfister and Janusz Kaminski), Streets teems with flavour and an authentic sense of place. These attributes are furthered by the richness of the story’s populace. They are, without question, among the most shaded prospects of Shea’s career. Impeccably performed by Applegate, the spunky, drug-addled Dawn is at once tragic and dynamic; a tortured soul gamely playing the cards she’s been dealt, fleeing a nightmare while her prospective beau – Mendenhall’s hungry, reluctant rich-kid, Sy – chases a dream that maybe, just maybe will benefit the pair of them. Even the supporting ensemble cut striking figures. They’re worn and real, teasing weighty backstories and deep-rooted motivations. I’d defy anyone not to cry during Streets’ emotionally ruinous coda.

Of course, the baser and nastier thriller aspects of Streets pack a wallop as well. A suspenseful and often disturbing film, the knuckle-whitening tension is heightened by Lottimer’s vivid depiction of badge-bearing evil. His compelling inhabitation appears incredibly socially conscious in retrospect, seemingly tapping into the rising apprehensions about Los Angeles law enforcement, before they’d come to a violent head in the city’s 1992 riots (which the aforementioned Naked Obsession invoked too, incidentally). The shotgun rape is stunningly icky, and the harrowing “goodnight” sequence, when Lumley offs a junkie girl, is heartbreaking. Thankfully, at the risk of spoilers, the bastard gets an electrifying comeuppance – and on route, there’s plenty of darkly comic levity, what with the murderous plod’s increasingly battle-damaged visage both illustrative of his rapidly splintering mental state and presented for grim, slapstick laughs.

[1] Streets landed in U.S. theatres on 19th January 1990. It opened in Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, and Kentucky before rolling out to Florida, Texas, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, New York, and, by June, California. It arrived on cassette on either side of the Atlantic via MGM/UA Home Video.