Matty champions Katt Shea’s barnstorming vampire drama.

A brilliantly weird chamber piece, Katt Shea’s DANCE OF THE DAMNED (1989) is, in effect, an erotic horror version of Before Sunrise (1995) — made half a decade before that film even existed.

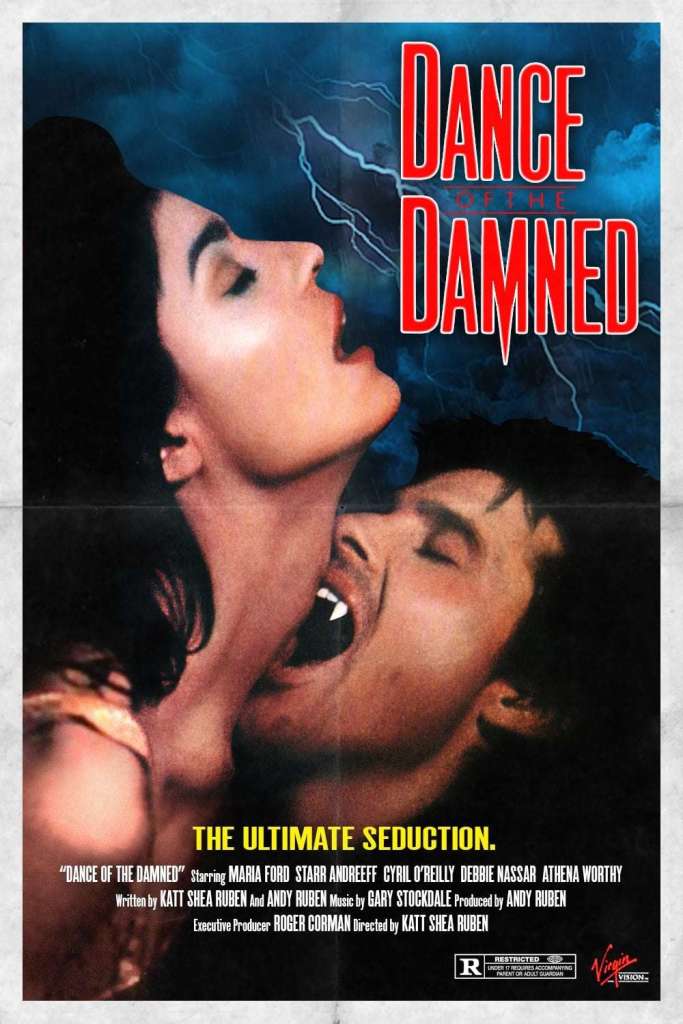

Shea’s sophomore feature, Dance of the Damned builds on the oneirism of Stripped to Kill (1987). While Shea’s debut veered towards the fantastic in terms of style and attitude, the wonderfully — if self-consciously — arty Dance of the Damned almost completely eschews Stripped to Kill’s gritty and more realistic footing. Instead, the film’s quietly affecting plot is anchored in a meticulously constructed netherworld; one poised between a blink and a tear — between life and death — and one where lapses in narrative logic can be excused by emotional authenticity. When watching Dance of the Damned there’s a sense that, for all its hip kookiness, this tale of a centuries-old vampire (Cyril O’Reilly) and a downtrodden stripper (Starr Andreeff) falling for each other (ish) over the course of a single evening is among the most unflinchingly honest love stories committed to celluloid.

Gorgeously lensed by Phedon Papamichael — who, post Dance of the Damned, became a key part of Shea’s creative arsenal for a spell, lensing Stripped to Kill II: Live Girls (1989), Streets (1990), and Poison Ivy (1992) — the film’s use of light, shade, and assorted textural devices (expressionistic sets, dry ice machines etc.) bolsters the dreaminess. Aesthetically, Dance of the Damned calls to mind those strange booze or substance-soaked nights whereupon mutual flirtation and obvious sexual tension quickly gives way to the unshakable feeling that maybe — just maybe — the curiously like-minded other person you’ve happened across might be your soulmate. Albeit, in the case of Andreeff, a soulmate whose blood you want to slurp…

Well written by Shea and then-husband/writing partner Andy Ruben, Dance of the Damned, a la Stripped to Kill and the rest of Shea’s best work, is stunningly character focused. At the script’s core is Shea’s defining auteur flourish — people in search of something — and the film only stumbles when it strays from the electricity of the dialogue, when it tries to throw in a little action sequence or, troublingly, a bit of casual misogyny. It’s not needed. Dance of the Damned’s greatest pleasure is seeing the excellent O’Reilly and Andreeff joust, toy, and, ultimately, ‘get’ each other during their city-wide, wee-hours prowl. According to Shea, O’Reilly was a last minute, lighting bolt casting decision:

“Cyril came in so late I thought he was delivering a pizza to my house,” Shea told TV Store Online. “It was really late at night and I thought “God, we’re never going to find my vampire”, and he walked in. He was the first one auditioned who didn’t sound like he was doing a stage play; and he didn’t sound like he was doing a period piece. He just talked like a real person and I said “Okay this is the guy!”.” [1]

As with Stripped to Kill and Shea’s next two features (Stripped II and Streets), Dance of the Damned was produced by Roger Corman; and, like Stripped to Kill, which begat Dance With Death (1992), the mogul remade the film with lesser results (as To Sleep With a Vampire (1993)). Dance of the Damned hit tape in the U.S. via Virgin on 19th April 1989, and eventually landed on cassette in the U.K. on 3rd June 1992, through Virgin and their pact with Columbia-TriStar Home Video.

Historically, Dance of the Damned also marks the screen debut of arguably the definitive B-movie starlet of the early ‘90s, the mighty Maria Ford. Legend has it that, when he surveyed Dance of the Damned’s dailies, Corman was so taken with Ford that he ordered Shea to place her front and centre of Stripped to Kill II, which started shooting — sans screenplay — days after Dance of the Damned wrapped, their productions separated by a weekend.

[1] Director Katt Shea Talks About Her 1980s Roger Corman Films, TV Store Online, 3rd February 2015 (since defunct, archived via Wayback Machine).