Matty profiles Katt Shea’s trendsetting murder mystery.

Katt Shea is an avowed De Palma and Argento nut.

Shea’s stated that it was the former’s work in particular that inspired her to pursue filmmaking in the first place. By her own admission, the actor turned director had a pair of real ‘pinch-me’ moments when she was cast in De Palma’s Scarface (1983) and subsequently hired to helm one of her best-known movies, The Rage: Carrie 2 (1999) – a sequel, of course, to the maestro’s iconic original.

Poorly received on release, Carrie 2’s stock has increased dramatically over the last quarter of a century. The film has finally found its audience. And while it hasn’t quite experienced Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982) levels of reappraisal just yet, the kinship Carrie 2 shares with the similarly-thunk Psycho III (1986) is striking. Another once neglected follow-up, Psycho III’s admirers likewise increase year to year. Many are now quick to hail the film’s ‘American Giallo’ sensibility and its nods to – yep – the likes of De Palma and Argento. As it happens, Psycho III also features Shea among its ensemble. In fact, the film actually played a vital part in the creation of her directorial debut, STRIPPED TO KILL (1987):

“I knew I was going to be directing Stripped to Kill, and that Psycho III would likely be my last acting job,” Shea told Fülle Circle Magazine. “Mike Westmore was my makeup artist, and he was instrumental in convincing [producer] Roger Corman to allow me to make Stripped to Kill, which required prosthetic makeup and which Mike was willing to build for me for cost. The movie involved a male posing as a stripper – this was long before The Crying Game (1992) – and Roger didn’t think that would be possible. So Mike was part of my arsenal that convinced him. So Psycho III was a key element in my directing career. How funny is that? The guy who won an Academy Award for makeup in Raging Bull (1980), exploding eyes and such, was applying my foundation and blush!” [1]

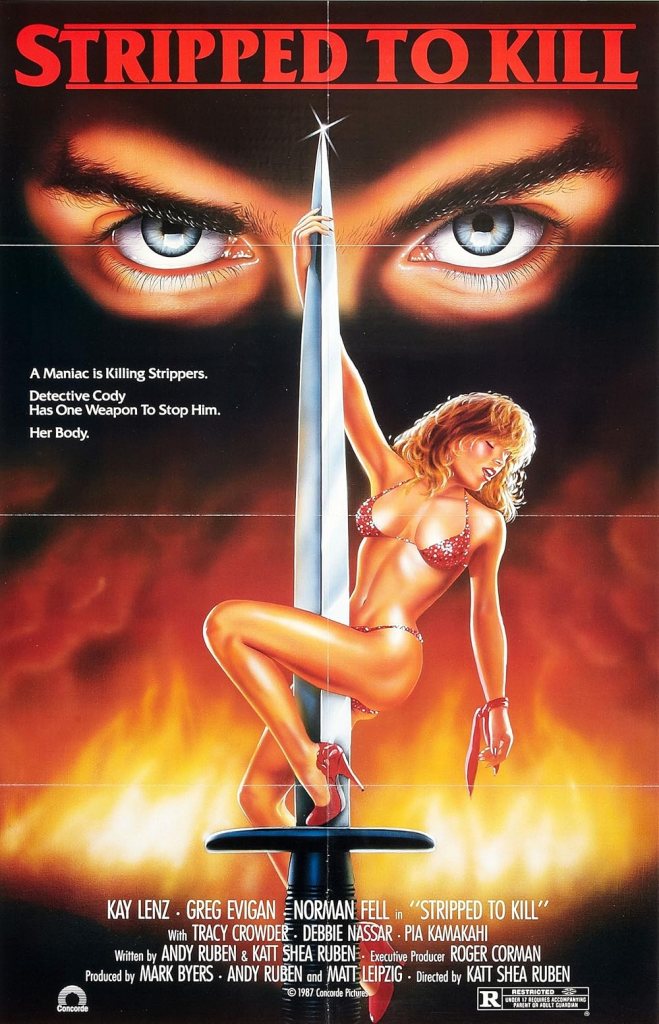

A visually arresting experience, Shea’s love for De Palma and Argento is obvious from Stripped to Kill’s opening strokes. Dripping with style, the film unspools in a peculiar heightened reality that’s part noir, part sleazoid nightmare. Bubbling with a dynamic yet purposefully uneasy colour palette, all icky earth tones, purples and – what else? – eye-popping deep reds, Shea juxtaposes the gritty luridity of the story – nasty murders taking place in and around a Skid Row strip club – with fanciful execution, imbuing Stripped to Kill with a succulent, almost fantastical edge; an approach she’d refine and wholly lean into across her next batch flicks, Dance of the Damned (1989), Streets (1990), and Stripped to Kill II: Live Girls (1989). With its designer violence, gender-bending hook, and emphasis on snazzy dance sequences (choreographed by Ted Lin), Stripped to Kill is, in essence, Dressed to Kill (1980) meets Suspiria (1977).

A mix as devilish as it sounds.

“I lost a bet with my writing partner [then-husband Andy Ruben],” said Shea of the film’s genesis. “He told me that mussels were poisonous at a certain time of year and you couldn’t eat them. I was like, “I’ve never heard that before.” I made a bet with him and if I lost, I had to go to a strip club. So it took me half an hour pacing back and forth in front of The Body Shop on Sunset Boulevard before I could go in. It was even at the point where Andy said, “Okay, you don’t have to do it.” And I went, “No, I lost a bet. I’m going.” They thought I was an off duty stripper or something and it was like, “Oh, my God, this is really going to be horrible. I don’t think I can do it.” I was ready to run out again. I was like a college girl. I was pretty sheltered, honestly. I grew up really sheltered. So I go in and I sit down and start watching these acts. These girls are coming out and they’ve got costumes and they’ve got a whole theme. They’re really dancing their hearts out. They were spinning around poles, and poles were not seen in movies yet. Nobody knew about this pole thing. I was just blown away by it and said, “I want to make a movie about this”.” [2]

Shea pitched Corman the project – then called ‘Deception’ – outside his offices, after ambushing him during his dinner break. As noted, the producer was initially resistant:

“It took me a year to convince Roger,” Shea reflected. “He just couldn’t believe a man could convincingly pass off as a woman. Finally I went to this club called La Cage Aux Folles on La Cienega Boulevard. It was the best of the female impersonators. These guys were just awesome. One of the gentlemen who was there came into Roger’s office with me. I set up a meeting. I said, “Roger, I’m going to prove to you that this can be done.” Roger said, “How’s he going to wear a g-string?” So this young man comes in with me and he’s so sweet. He sits down and he’s really nervous because it’s Roger Corman. He knows who Roger Corman is. And then he just goes into the most graphic, gory detail about what he does with his junk to get it in there. So Roger turns purple and orders us out of his office. He goes, “You can do the movie but just get out.” Then he phones me two hours later and goes, “I’ve changed my mind.” I’m not even yelling at him. I go, “No, you said I can. I’m doing it. You can’t take it back.” And so then he let me do it!” [2]

Hinging on the same ‘female cop goes undercover as an exotic dancer’ premise as Trans World Entertainment’s Catch the Heat (1987) (here, mind, the device is deliberately employed to mirror the killer’s M.O.), Stripped to Kill’s dramatic clout is defined by its rich character focus. Shea’s later standouts – Dance of the Damned, Streets, Poison Ivy (1992), the aforementioned Carrie 2 – teem with shockingly honest depictions of flawed individuals desperately seeking meaning and purpose; an auteur flourish Stripped to Kill clearly established. And though, as a collective, the denizens of Shea’s cinema tend to exude a cartoon-y bolshiness and exhibit a few extravagant tics and wrinkles, the bulk are nonetheless relatable. Again, Stripped to Kill lays the groundwork. The gimmickry of the killer’s presentation – which, in addition to the role’s De Palma and Argento winks, invokes the Psycho (1960) universe as well – is juxtaposed with their weighty psychological motivations; and the ‘tough cookie’ attitude of star Kay Lenz’s tomboy detective is a shield deployed by a complicated, vulnerable woman reluctant to let her guard down. In a satisfying bit of symmetry, the killer and Lenz – who, essentially, does the inverse of the perp she’s chasing, becoming more openly feminine – are both pretending to be something they’re not in order to thwart their loneliness. Shea and, indeed, co-scripter/producer Andy Ruben, would continue to harness parallel character development techniques in their equally well-written mini-epics Dance of the Damned and Streets.

Shot October and November 1986 and beginning its U.S. theatrical run in Alabama on 10th April 1987 [3], Stripped to Kill quickly became a video store fixture when it landed on tape on 29th July 1987 via Corman’s distribution deal with MGM/UA (cf. The Nest (1988), Not of This Earth (1988), Bloodfist (1989)) [4][5]. A hearty earner, the film was, as mentioned, sequelised by Shea and its success was singlehandedly responsible for initiating Corman’s wave of titty-bar programmers; a grungier subset of the DTV erotic thriller, typified by such pictures as Dance of the Damned (which, incidentally, Shea made back-to-back with Stripped II), Naked Obsession (1990), Stripteaser (1995), and a cheeky Stripped to Kill remake, Dance With Death (1992).

“Roger still hires apprentice filmmakers to photograph insert shots in L.A. strip clubs,” Shea chuckled to Femme Fatales. “And I bet they’re cursing me the whole time!” [6]

[1] From Corman to Classes: A Conversation with Katt Shea, Fülle Circle Magazine, February 2009.

[2] How the Director of ‘Poison Ivy’ and ‘Stripped to Kill’ Reinvented Nancy Drew for a New Generation by Fred Topel, Slash Film, 29th March 2019.

[3] By the end of April, Stripped to Kill was playing Georgia before moving on to Tennessee, Kentucky, Pennsylvania and Florida in May, and Texas, California and New York in June.

[4] Funnily, Stripped to Kill hit cassette the same day as Steve Miner’s House (1986). House also starred Kay Lenz and was produced by Corman’s old outfit, New World Pictures.

[5] Stripped to Kill went straight to video in the U.K., surfacing through MGM/UA on 12th October 1987.

[6] Katt Shea: Actress Turned Director by Dan Scapperotti, Femme Fatales, Vol. 5, No. 12, June 1997.