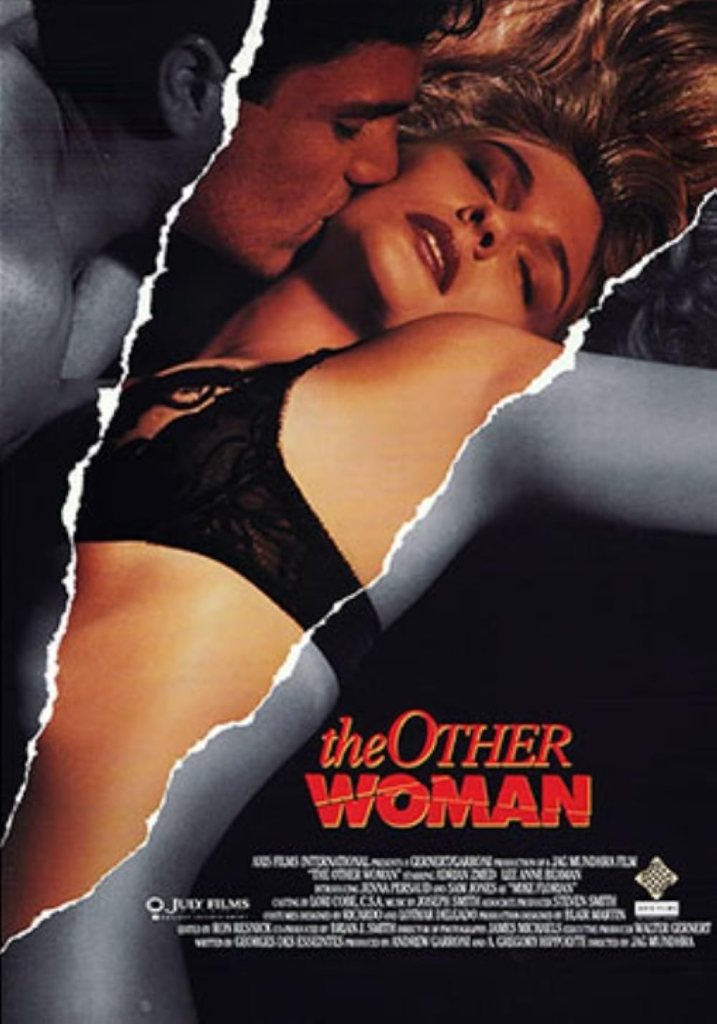

Matty looks at a solid erotic thriller that bridges the gap between two of the genre’s biggest proponents: Jag Mundhra and Axis Films International.

By the time Night Eyes (1990) blew up on cable and video, Jag Mundhra had pumped out Last Call (1991) and Legal Tender (1991), and passed on the chance to helm the trendsetting erotic thriller’s sequel in order to make Vishkanya (1991) in India. The experience was a disaster Mundhra described as six months of his life wasted.

When he returned to Los Angeles, Mundhra made THE OTHER WOMAN (1992).

An important movie in Mundhra’s development, The Other Woman: is the first Mundhra film without Ashok Amritraj as producer since slasher romp Hack-O-Lantern (1988); marks a fascinating union between the erotic thriller auteur and another key purveyor of the form, Gregory Dark, Walter Gernert and Andrew Garroni’s Axis Films International [1]; and should be considered the work that put Mundhra on the T&A footpath for the rest of the ‘90s, after jumping between the genre (Night Eyes, Last Call) and more conventional thrillers (The Jigsaw Murders (1989), Eyewitness to Murder (1989), Legal Tender) for the first years of the decade.

Three points of trivia for Mundhra’s third erotic proper – fitting, then, that The Other Woman concerns itself with a love triangle. Scripted by Axis regular Georges des Esseintes – a likely pseudonym for someone [2] – the plot finds prudish journalist Jessica (Lee Anne Beaman) discovering that her husband (Mundhra’s Eyewitness to Murder collaborator, Adrian Zmed) is having an affair with a mysterious beauty (Juliet Reagh, billed as ‘Jenna Persaud’). Naturally, Jessica undergoes a sexual awakening of sorts as she tries to figure out who the titular temptress is.

Better than Night Eyes, but a rung below Last Call, and still a few notches away from the majesty of subsequent standouts Wild Cactus (1993), Improper Conduct (1994), Irresistible Impulse (1996), and Sexual Malice (1994) (Mundhra and Axis’ second and final teaming), The Other Woman is a solid offering which veers close to great. The script is largely well written. Where it stumbles is with the straighter thriller trappings that bookend the main narrative; a subplot embodied by the hamming of Sam Jones as a slimy businessman-cum-suspected killer. Alongside some ill-suited, noir-ish narration, it’s almost as if Mundhra and Axis thought The Other Woman’s character-focused stretches wouldn’t fly without a bit of pantomime oomph behind them. Fact of the matter is The Other Woman is at its best when it’s being a domestic sex drama.

Previously appearing in Axis’ Mirror Images (1992), the wholesome-looking Beaman does a fine job conveying Jessica’s complexities. Post The Other Woman, the star became a real Mundhra regular, featuring in Tropical Heat (1993), Improper Conduct, Irresistible Impulse, Tainted Love (1996), and Shades of Gray (1997). Though the rest of the cast aren’t anything to shout about – a point compounded by patches of hokey dialogue – Mundhra relates the non-Jones portion of The Other Woman’s story with authority, slowly piling on the intrigue and drip feeding us information. Several moments don’t play as you’d necessarily expect, and the scenes of horizontal dancing are suitably crotch-quivering. Among the highlights: voyeurism; a pair of stunningly presented lesbian tangles (including a brilliantly sacrilegious flashback explaining Jessica’s repression); and a gloriously absurd sequence involving Reagh’s hooters getting splashed with milk.

Lensed by James Michaels, with whom Mundhra would team again on Improper Conduct, and sporting a studious/observational quality reminiscent of Steven Soderbergh’s indie smash sex, lies, and videotape (1989) – one of VHS erotica’s most unacknowledged influences – The Other Woman was released on video on either side of the Atlantic by Imperial Entertainment. A frequent peddler of Axis’ wares, Imperial issued the film in the U.S. on 5th August 1992, two and a half months after they nudged the shingle’s Secret Games (1992) onto shelves, and a month before they unleashed Axis’ magnum opus, Night Rhythms (1992).

The Other Woman hit the U.K. on 28th April 1993. Within the same month, Medusa facilitated the British bow of Axis’ second masterpiece, Animal Instincts (1993), and within the same ten month stretch, Imperial released Axis’ The Pamela Principle (1992) (February); Columbia-TriStar released Night Rhythms (Jan) and Axis’ third masterpiece, Body of Influence (1993) (June); and 20:20 Vision released Axis’ Sins of the Night (1993) (October), Mundhra’s inexcusable folly, L.A. Goddess (1993) (May), and Mundhra’s magnificent Wild Cactus (October).

[1] While the ever brash Dark claims he innovated the erotic thriller with his “bored housewife flick” Carnal Crimes (1991), Gernert and Garroni freely cite Night Eyes among their inspirations for Axis.

[2] Potentially a highbrow literary allusion, Georges des Esseintes is the name of a character in Joris-Karl Huysmans’ 1884 novel, À rebours (‘Against the Grain’). In the novel, des Esseintes is a wealthy, reclusive, and effete noble who pursues a life of sensualism and decadence; themes central to his screenwriting namesake’s Axis assignments (cf. Mirror Images, Secret Games, Animal Instincts).