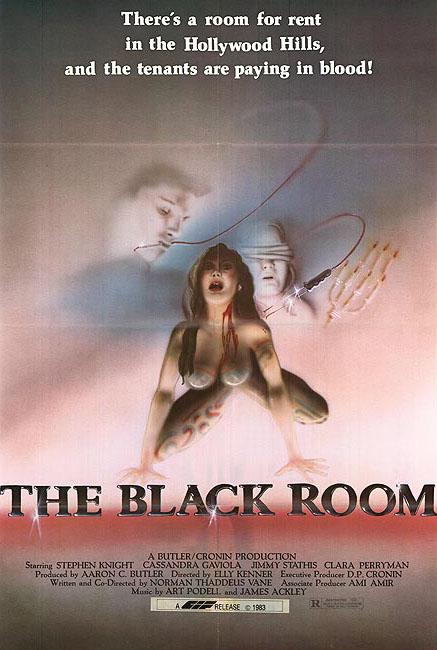

Matty hooks up with one of his favourite horror movies.

In his 1977 masterpiece Martin, George A. Romero used vampirism as a metaphor for teenage despondency.

In THE BLACK ROOM (1982) bloodsucking is allegorically employed for more grown-up reasons: as a means to explore the complexities of relationships, monogamy, and promiscuity post free love but pre AIDS.

A legendary swordsman himself, The Black Room’s scripter and co-director, Norman Thaddeus Vane — a fascinating minor league auteur known for the wonderfully ghoulish slasher flick Frightmare (1983) — was a regular on the London-New York-Los Angeles party circuit in the ‘60s and ‘70s. It was his playboy lifestyle as, at various times, a nightclub owner and editor of the U.K. branch of Penthouse Magazine that served as his inspiration when he started writing The Black Room. As noted by author Stephen Thrower in his mighty tome, Nightmare USA: The Untold Story of the Exploitation Independents, it was during Vane’s stint at the notorious men’s rag when he repeatedly cheated on his then-wife, sixteen year-old model Sarah Caldwell, with numerous centrefolds at a venue like the eponymous chamber.

Upping the sexual undercurrent already present in the vampire genre, The Black Room switches fangs for an apheresis machine, and swaps a Transylvanian castle for a plush homestead in the Hollywood Hills. Our Dracula is Jason (Stephen Knight): a handsome and charismatic photographer — Lugosi, Lee and Langella rolled into one, spiked with the same kind of irresistible menace invoked by Chris Sarandon in Fright Night (1985) — stricken with a rare blood disease he manages by draining others of their plasma. “He’s been sick his whole life, ever since he was a child,” explains Jason’s sister, Bridget — The Black Room’s singular answer to Drac’s buxom brides. “He had to constantly replenish his blood. Every sixty days. Then once a month. Now, it’s twice weekly.” Essayed by the stunning Cassandra Gava (best remembered as the sexy witch in Conan the Barbarian (1982) and credited here under her real name, Cassandra Gaviola), Bridget is Jason’s carer, muse, and, it is teased, lover. She’s also his accomplice, helping the tanned hunk lure, kill, and dispose of his unwitting donors.

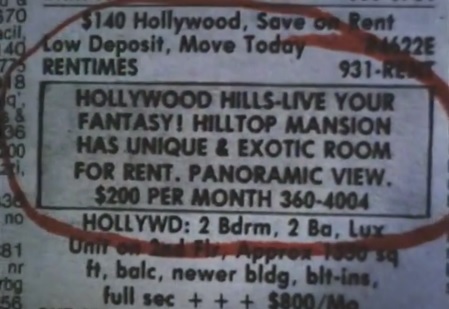

Calling to mind Paul and Mary Bland, the jocular antagonists at the heart of Paul Bartel’s conceptually twinned black comedy, Eating Raoul (1982), Jason and Bridget have determined horn-dogs to be ideal victims. Renting out the titular space in their house, the siblings take their pick from the randy denizens who come — quite literally — to occupy it. “Restrictions?” says Jason. “None. This isn’t the YMCA. What the former tenants usually did was phone first; I’m always working in my studio. If you like, I can just pop in, light the candles, pour the wine — the rest is up to you.”

Into their set-up steps Larry (Jimmy Stathis) and Robin (Clara Perryman): a couple whose marriage is growing stale. Though clearly still in love, their sex life has taken a beating due to a general ‘seven-year itch’ and their bedroom gymnastics frequently being interrupted by their two hyperactive children. Frustrated, Larry learns of Jason and Bridget, becomes their latest tenant, and elects to utilise The Black Room as his base for some much-needed afternoon delight with a bevy of random women.

Given his penchant for co-eds, it’d be easy to think Larry an irredeemable sleaze. Instead, the equally questionable Vane — worth repeating: he married a sixteen year-old — throws a curveball: suddenly, Larry’s illicit dalliances stoke the fires of wedded passion again. Relaying his Black Room visits to Robin, she, at his insistence, treats them as fantasy. Foreplay. Dirty talk. Seemingly as unsatisfied with Larry and he is with her, Robin’s inner vixen is quashed by his strange sense of coital morals: it’s OK for him to get fruity in his hired hump den, but anything other than missionary on the marital mattress is strictly off limits with the Mrs. “Why aren’t you ever [kinky] with me?” Robin asks. “Because I love you,” Larry replies.

Larry’s attitude to sex and fidelity is the meat of The Black Room’s narrative. Robin, however, has the most compelling arc. “Why don’t you do to me what you said you did to that girl you took to that black room?” she questions upon discovering her husband’s fairy tale shag-pad is, in fact, real. “I couldn’t do that to you, it wouldn’t be right. You’re my wife,” he curtly responds. Barely masking her hurt and — crucially — her disappointment, Robin persists: “I don’t want to be your wife when we make love. I want to be your whore.” Larry, of course, tries to weasel out of it: “I don’t see you in that room,” he says. “You don’t belong there.” Naturally, Robin is soon exploring the place herself, and her vulnerability and desires are quickly brought into question by the malevolent Jason: a sanguine slurper who genuinely enjoys playing with his food…

A character focused slow burn (according to Vane, he was responsible for “the drama” and co-director Elly Kenner — a young Israeli talent drafted in to appease the film’s chief backer, an Israeli businessman — “the look”), The Black Room is powered by mood and suggestion rather than graphic splatter. That said, when the claret does flow (a neophyte gig for gloop and latex specialist Mark Shostrom) it’s thrilling stuff. The Black Room doesn’t skimp on the horror, with a five minute transfusion sequence the undoubted highlight. The sole showing of Jason’s ritualistic process, it’s a perfect and perversely titillating moment. Brimming with a twitchy, tense energy, the transfusion scene begins with a heartbeat pulsing on the soundtrack and descends into orgasmic ecstasy, the line between pleasure and pain — between life and death — blurring in a frenzy of rhythmic cutting and fetishistic imagery.

The Black Room itself is also impressively realised. Seductive yet creepy, cinematographer Robert Harmon’s simple but effective use of a kitschy glowing coffee table, candlelight, and inky shadows conjures an atmosphere that bubbles with eroticism and danger. A former stills photographer, Harmon subsequently parlayed his keen eye and flair for the macabre into a pair of brooding road shockers, The Hitcher (1986) and Highwaymen (2004), when he transitioned to the director’s chair. The superb Steadicam work of Andrew ‘Jeff’ Mart adds further spectral elegance. Supposedly the first person in the world to privately own a Steadicam rig, Mart famously had a special, one-handed bicycle that he’d use for daredevil shots, and he would ply his trade across a wealth of goodies — Pumpkinhead (1988), The People Under the Stairs (1991), Full Eclipse (1993), Hard Target (1993), and Kickboxer 4: The Aggressor (1994) among them — prior to his death at the age of sixty-six in 2009.

For trivia nuts, The Black Room is notable for being one of the earliest films to feature scream queen Linnea Quigley. A few years away from hitting paydirt on The Return of the Living Dead (1985), Night of the Demons (1988), and Sorority Babes in the Slimeball Bowl-O-Rama (1988) et al, Quigley’s small role as babysitter Milly is an interesting echo of her even earlier turn as Bondi’s Mother in another leftfield vampire(ish) romp, Don’t Go Near the Park (1979). Indeed, despite its significantly shoddier quality, broadly speaking the vaguely similar Don’t Go Near the Park would make for a diverting companion piece to The Black Room — a notion accentuated by their shared status as video nasties here in the U.K.

Lensed in ten days on a $40,000 budget in January 1981, The Black Room was passed uncut for British theatrical release in November 1982 (with an X rating) but found its 1983 cassette (from Intervision) listed as a Section 3 nasty (a title liable for seizure but unable to be prosecuted as obscene material). Alas, where the bulk of pictures caught in the scandal have ascended to the rank of cult or classic, The Black Room remains at the obscurer end of the video nasty scale. Such a tragic fate probably won’t change either: The Black Room’s original negative is rumoured to be lost, and the rights to it are purportedly mired in a legal tangle of hellish proportions.

A depressing conclusion to a remarkable film.