Dave casts his voyeuristic eyeballs over Shem Bitterman’s study of one man’s depravity. Featuring an interview with the playwright himself!

There’s a long line of plays that have been adapted for the screen, either with their creators or without – but as far as I can recall, PEEPHOLE (1993) is the first to take every single component from its original production and use them for the movie version.

Opening in mid-November 1991 at the Olio on Sunset Boulevard for a two week spell, L.A. Weekly’s Theatre Calendar questioned if Peephole‘s motive was “simply the scheme of a playwright bent on shock” [1]. Critic Ray Loynd, meanwhile, called it “dark, edgy, and demented” before going on to question the show’s credibility. In any case, it garnered enough good notices for playwright Shem Bitterman to reunite his cast six months later and lay it all down on film.

Virtually every performer from the play is here. There’s Patrick Husted in the lead role of a character known only as The Psychiatrist, a prison shrink who befriends one of the most repulsive inmates, a paedophile called Rick (a stunning turn from Rick Dean). Rick is eligible for release – but before he gets out, he sends The Psychiatrist on a mission to check on his girlfriend, a hooker by the name of Sheena (Kristen Trucksess), which gives way to the two becoming intimate. All of these sordid shenanigans take place against the backdrop of a predatory serial killer, which leads to the investigative nose of a hardboiled cop (William Dennis Hunt), who’s paying close attention to our nameless analyst.

A graduate of New York’s High School of Performing Arts and Julliard, Bitterman went on to receive an MFA in playwriting from the University of Iowa. Since, he’s won awards as varied as the Pen USA Literary Prize and the Los Angeles Times’ Critics Circle Award. Despite what appears to be a highfalutin background, chances are that most genre fans will recognise Bitterman’s name as the co-writer of Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myers (1989).

Bitterman, then, must have wanted to direct for some time.

“Actually no,” is the surprising response from the dramatist. “In fact, I had never been on a film set when I made it! I had another film made previously too, directed by Gary Winick, and released as Out of the Rain (1991), but I hadn’t been on set for that either.”

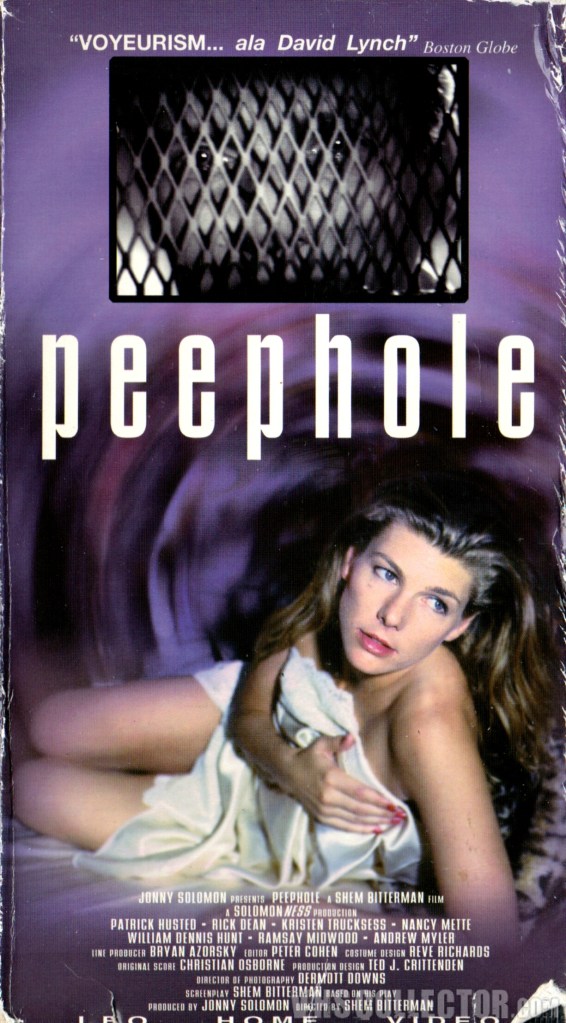

Peephole is a strange fruit. Accurately declaring on its home video art to be “where normal and deviant merge”, the film offers a voyeuristic look beneath the flannel-suited façade of a mundane man who’s daily exposure to societies perverse and twisted individuals seeps slowly into his psyche.

“At the time, as a playwright, I was very interested in approaching themes – like society’s hypocritical views on good and evil – through genre,” says Bitterman. “Accordingly, this was a ‘mystery’ play, a marrying of the religious and the noir.”

The cast are sublime. The number of times they’ve spoken each line and delivered each scene is reflected in how smooth and assured everything is; all the while the camera floats around with the grace of well-drilled dancer.

“I was, believe it or not, influenced by Bergman. I wanted long takes and as few edits as possible. Bergman was very theatrical in his approach to film… I didn’t know much about the practical aspects of making a movie – a play lives very much in the audience’s imagination, but in a movie everything has to be visually represented, which was a tough adjustment for me.”

“I was going for a dark and shadowy look but I didn’t seem able to fully communicate what I wanted to my DP – and that was my fault entirely. I didn’t know much about key lights or lighting in general. If I had, I would have lit it quite differently, more like the play, which was lit by the brilliant Kevin Adams who went on to win four Tonys. His design was done with only dangling lightbulbs and household dimmers – a technique he used to much affect later on Broadway for the revival of Springs Awakening.”

Technical approbations aside, Peephole is a challenging endeavour; a deliberately difficult patience tester that will leave a swathe of its audience miffed and adrift.

“In the play, we very much leaned into the idea of ellipsis: of the audience not having the ability to see the entire picture,” offers Bitterman. “I wanted the kind of the impression you get when you are on the street, walking by a lit window at night. There is something going on within the room, a drama being played out, and everything that is happening between the people is quite intentional, but the endings and beginnings are snipped off – the exposition is excluded. To me it was fun to tell a story that way, without exposition.”

A festival favourite, Peephole took home the Finalist Award in Houston and received high acclaim in Florence. In terms of VHS, the film crept into the living rooms of unsuspecting video store patrons sometime in 1994 courtesy of Leo Home Video – an eclectic label home to Schlock Pit favourites like David Michael Latt’s Killers (1997) and Richard Gabai’s Virtual Girl (1998).

For Bitterman, though, the most abiding memory of his Peephole cinematic endeavour is the production being stuck right in the centre of the L.A. riots.

“The entire city was ablaze and we had to shut down production for ten days!

We were shooting in an abandoned department store in downtown L.A. – the place where we had built all our sets – when fires broke out all around us. In a time of civil unrest or riot, your insurance is no longer valid, so we had to escape with all the camera equipment in our private cars. As we came around Venice, heading west, a man was spraying the air with a machine gun and the Pep Boys auto shop was on fire. A burning tire rolled across the road and looters were emptying the place. Ash was falling down all around us.”

“Needless to say, we didn’t stop at any red lights!”

U.S. video art courtesy of VHS Collector

[1] Theatre Calendar, L.A. Weekly, 14th November 1991.

[2] Peep-Hole Fails Credibility Test by Ray Loynd, Los Angeles Times, 16th November 1991.