Matty chats to director Peter Manoogian about his distinctly un-Charles Band-like Empire flick.

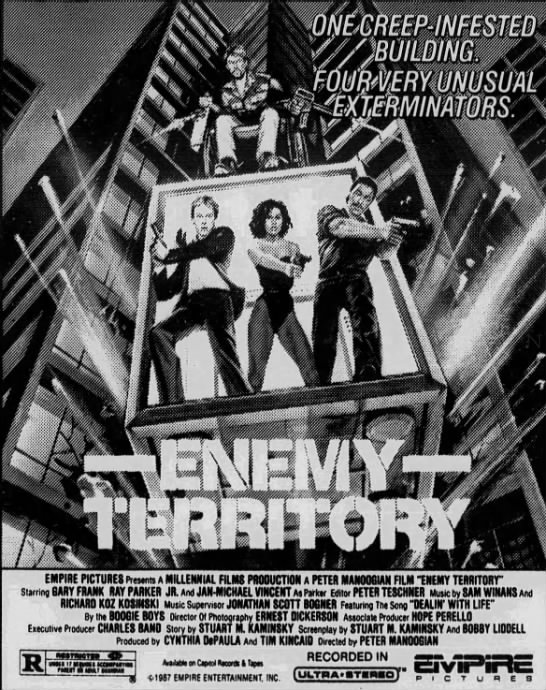

Thrilling, snappily paced and boasting a wealth of intellectually nourishing pokes at such weighty topics as greed, class and race, ENEMY TERRITORY (1987) is a hidden gem within Charles Band’s mammoth filmography. It’s also one of the Empire Pictures and Full Moon impresario’s most atypical offerings. The Dracula fixation of its villain, gang leader The Count (Tony Todd), aside, this criminally underseen action flick — think Assault on Precinct 13 (1976) in a tenement [1] — is completely free of the waggish fantastical elements that exemplify the majority of Band’s confections.

“It was very different to your usual Empire movie,” says helmer and former Band stalwart, Peter Manoogian. “Gritty, urban — there’s no little creatures or elaborate special FX or anything! Charlie wasn’t that keen on it but his wife and creative partner at the time, Debra Dion, she loved the script. Loved it. She was really passionate about it.”

As detailed by critic and Schlock Pit pal Dave Jay in his seminal tome, Empire of the Bs: The Mad Movie World of Charles Band, Enemy Territory — which, according to Manoogian, began life under the name ‘Show No Mercy’ — was originally set in Chicago and unfurled in the projects of Cabrini-Green. Then a hotbed of real-life gang activity, Cabrini-Green would be immortalised onscreen a few years later in Bernard Rose’s horror classic Candyman (1992) which, amusingly, saw the aforementioned Todd cast as the eponymous fiend.

Having risen up the Band ranks — first as an assistant director on pre-Empire opus Parasite (1982), then as a production executive on the likes of Swordkill (1984) and Trancers (1984) before transitioning to directing with a segment of fantasy anthology The Dungeonmaster (1984) — Manoogian was looking to follow his feature-length debut, natty sci-fi adventure Eliminators (1986), when the initial iteration of Enemy Territory caught his eye. Penned by Stuart Kaminsky in the wake of the author, journalist and film academic’s dialogue work on Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America (1984), Manoogian recruited a screenwriter pal — masked by the pseudonym ‘Billy Liddell’ on the finished movie due to WGA rules — to overhaul Enemy Territory when Band finally gave it the go ahead.

“We retooled the structure of it, and relocated it to New York,” Manoogian explains. “What happened was, Charlie had a deal with this New York filmmaker called Tim Kincaid. Tim was making these tiny movies for Charlie, a ‘shoot ‘em in five days for $50k’ kind of thing. They were really trashy but Charlie thought the technical side of them was OK enough — certainly OK enough to convince him that Tim could at least put a movie together, you know? [laughs] So Charlie agreed to let me make Enemy Territory as a New York movie. I went out there and Charlie let me take a producer, Hope Perello, with me. I’d worked with Hope on Eliminators and Deadly Weapon (1987) and she was just really, really good at her job. We met Tim and his girlfriend and co-producer, a woman named Cynthia De Paula, and it became pretty obvious pretty quickly that it wasn’t going to work. Tim and Cynthia were only used to these miniscule budgets and schedules, and we ended up doing Enemy Territory over four weeks for something like $800,000.”

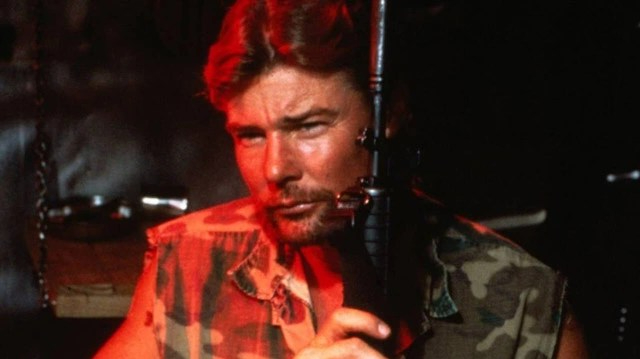

With Manoogian spiking his excitingly rendered scenes of running, shooting and scuffling with a hearty dose of buddy-cop comedy (the funniest stuff involves the narrative McGuffin, a big insurance policy payment made in cash, repeatedly getting used for various life-saving services as the film’s chalk n’ cheese heroes traverse an extremely dangerous Manhattan tower block), Enemy Territory is part claustrophobic siege caper (a la the director’s subsequent Band epic, Demonic Toys (1992)), part epiphanic odyssey. Essentially chronicling a socially conscious awakening, Manoogian charts the evolution of highly strung insurance agent, Barry (soap perennial Gary Frank), from passive aggressive racist to someone agreeable, accepting, and human. A white and entitled doofus, Barry’s teaming with a black telephone repairman, Will (actor/singer/songwriter Ray Parker Jr., still riding the wave of his 1984 soundtrack smash, Ghostbusters), is presented as less a chance encounter, more a necessity. Tough and down-to-earth, Will’s status as protector is rapidly eclipsed by the character’s true purpose. As his trade implies, the wire tapper is an expert at establishing and bonding lines of communication. Thus, when Barry inadvertently unleashes the wrath of Todd’s flamboyant warlord and his fleet of heavily-armed ‘Vampires’ (“Show me your fangs!”), Will’s plan to get him and his feckless charge out of the labyrinthine hell they’re trapped in becomes a Christmas Carol-esque tale of transformation as the pragmatic arse-kicker introduces the tetchy broker to a slew of kind-hearted tenement residents as victimised by The Count as they are. Even Jan-Michael Vincent’s crippled Vietnam veteran: a broken, paranoid husk who, for all his bigoted rhetoric, ultimately does what’s right by the only people that accept him.

“Here’s a weird thing,” Manoogian chuckles, nervously. “It’s kind of ironic since we cast Jan-Michael. He came with a lot of problems due to his own drinking. But when we got to New York, Tim wanted us to use his DP and we couldn’t do it because the guy was an alcoholic. So Hope looked around and found Spike Lee’s cinematographer, Ernest Dickerson, and he was just wonderful. I loved the style and energy he had, and he was really, really into the movie — the feel, the texture of it, everything. He was fantastic. But when we got Ernest, Tim and Cynthia sort of vanished from view. They might have been credited as Enemy Territory’s producers, but it was me and Hope orchestrating the show, and Charlie just let us run with it. Sadly, we didn’t have the money to get the ending I wanted. All the residents were meant to come together to topple the gang but I can’t complain. To this day Enemy Territory is my favourite out of all my movies. I love it. And Debbi loved it. I just wish it got the kind of release it should have got. It’s never found its audience, which is a shame.”

Enemy Territory opened theatrically in New York on Friday 22nd May 1987. A review in the same day’s copy of the New York Daily News was savage, labelling it “unpleasant” and “racist”. Subsequently, as Manoogian explained in Empire of the Bs, picketing and protests took place across the five city cinemas screening the film. The groups responsible took umbrage with what they perceived to be Manoogian et al fuelling the stereotype of violent black gangs, completely ignoring Enemy Territory’s social conscience and its overarching themes of community and finding common ground despite gross annual income and skin colour. Thankfully, the film was better received in Los Angeles five months later, but, by that point, its fate was sealed. Enemy Territory schlepped to cassette stateside via CBS in December ‘87, and was released straight-to-tape here in the U.K. by Entertainment in Video — a frequent purveyor of Band’s output. It’s never arrived on DVD and, as of this writing, no Blu-ray is forthcoming.

Manoogian nailed it.

A shame indeed.

[1] A further John Carpenter allusion is supplied by the film’s closing song, Friend or Foe by Harlem-based hip hop group the Boogie Boys. The 1986 track samples the horror master’s iconic Halloween (1978) theme.