Our Gregory Dark celebration continues with Matty’s profile of the helmer’s compelling sci-fi thriller.

“I play a corrupt megalomaniac,” G. Gordon Liddy told the Associated Press in August 1989, just as STREET ASYLUM (1990) — then called ‘The Squad’ — was about to start shooting. “I’m a former police officer now running for mayor who has formed a sinister alliance with a female mad scientist. I am also a sexual pervert… If you’re seen as a credible villain by producers, directors and casting people you’re very fortunate.”

Not that anyone would need much convincing. One of the key figures behind the Watergate scandal, Liddy spent the years following his incarceration — whereupon he served fifty-two months of a commuted prison term — embellishing his infamy. The fed turned conspirator penned an eyebrow raising memoir, became a sought-after public speaker and, before reinventing himself as a conservative shock jock, parlayed his status as America’s preeminent bad guy into a series of guest roles in TV shows such as Miami Vice and MacGyver.

“I only play villains,” Liddy later joked about his screen career. “That way, I don’t have to act. I just show up.”

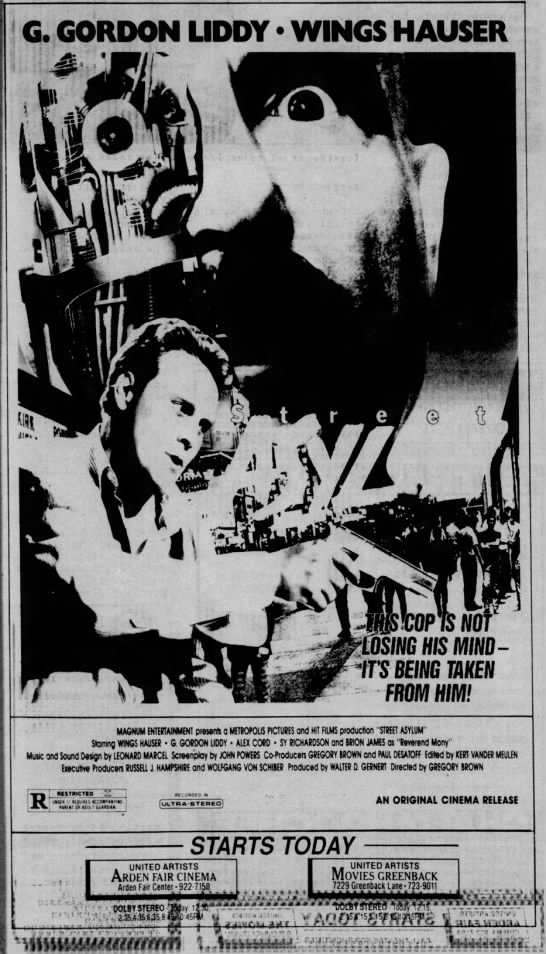

Though Liddy’s character in Street Asylum benefits more from the outrageous, near actor-proof definition provided by John Powers’ robust comic book scripting than the die-hard Republican’s actual performance, his casting garnered a fair bit of publicity for the film’s producer, Walter Gernert, and director, Gregory Dark [1]. Their second ‘straight’ feature, the porn iconoclasts viewed Liddy’s recruitment as both conceptually fitting given the futuristic Street Asylum’s themes of duplicity and manipulation, and a Corman-esque blast of exploitation showmanship. Indeed, so enamoured were Gernert and Dark with providing Street Asylum an attention-grabbing hook that, initially, they also offered the “female mad scientist” part to another famous figure, socialite Cornelia Guest. While the ‘80s It girl’s interest evaporated in the wake of script revisions (resulting in her being replaced by Marie Chambers), the gimmickry kept Street Asylum in mainstream view long enough to warrant Gernert booking the finished film for theatrical playdates in Des Moines, Sacramento, Pittsburgh and Detroit ahead of its VHS release (via the mogul’s own tape label, Magnum Entertainment) in June 1990 [2].

By that time, Liddy was refusing to help Gernert and Dark promote it. According to Dark, throughout the entirety of its making, Liddy, somehow, thought that Street Asylum was a right-wing call to arms; a battle cry in favour of capitalism and hardline policing. When the penny dropped during a private screening, the devout Nixonite was aghast that this scintillating sci-fi thriller was, in fact, a RoboCop (1987) scented anti-capitalist, anti-police state satire.

“Listen, the guy was a pleasure to work with, but he saw the film and just won’t do any publicity at all,” Dark told Newsday. “The movie’s about [the perils] of reacting to violence with violence. I guess in his mind that’s reasonable. I didn’t have any problems with him other than his political beliefs, which are carried to the end of the universe.” [3]

Reuniting Gernert and Dark with key cast and crew from their previous sci-fi outing, Dead Man Walking (1988) — chiefly: stars Wings Hauser, Brion James and Sy Richardson; script consultant John Weidner, who, along with writing partner Ken Lamplugh, helped refine Street Asylum’s screenplay; cinematographer Paul Desatoff; and editor Kurt VanderMeulen — the film builds upon that earlier offering with wit and style. The post-apocalyptic Dead Man Walking wasn’t an aesthetically ugly picture by any stretch. It sported a distinctive and immersive look rooted in the grit and gristle of Gernert and Dark’s pioneering XXX epics (Black Throat (1985), New Wave Hookers (1985) etc.). There’s still a snotty, rock n’ roll edge to Street Asylum. That, in itself, is a trait nestled deep in Dark’s DNA. Here the helmer employs a more formal approach, unleashing the same kind of polish and pizzazz that would go on to typify his and Gernert’s subsequent erotic thrillers (Mirror Images (1992), Night Rhythms (1992), Body of Influence (1993) et al), his later music videos (for artists such as Britney Spears, Linkin Park, and The Calling), and his biggest budgeted production, glossy WWE-backed slasher flick See No Evil (2006).

Despite Street Asylum’s plot — in which Hauser’s L.A.P.D. officer is lured into a wacky crime-fighting unit known as The S.Q.U.A.D. (an acronym almost as good as C.H.U.D. (1984) — “Scum Quelling Urban Assault Division”!) — skirting close to predictability, the film’s cookie-cutter mystery/conspiracy elements feel less important than its manic ‘of the moment’ energy and sense of spectacle. Like its zeitgeist-surfing contemporaries Predator 2 (1990), Naked Obsession (1990), and The Taking of Beverly Hills (1991), Street Asylum is a devilish entertainment that taps into the social and economic tensions that were bubbling in Los Angeles in the build up to the 1992 riots. Watching Hauser unravel against a backdrop of civil unrest and Cronenberg-tinged body horror is great fun, and witnessing Liddy surrender to his twisted politico’s kinky desires is a delirious experience. The acting honours, however, belong to Richardson. The Alex Cox regular is hypnotic as the cackling Joker: a S.Q.U.A.D. member who, in a series of screamingly funny scenes, uses his homosexuality and his blackness to intimidate a frazzled stool pigeon.

[1] Dark directs under his real name, ‘Gregory Brown’.

[2] Transparency: Liddy, alas, isn’t revealed to be a cyborg as Magnum’s deceitful poster promises. In the U.K. Street Asylum was issued by Medusa in November 1991, marking the beginning of an output deal that would go on to include them distributing Gernert and Dark’s Carnal Crimes (1991), Mirror Images, Secret Games (1992), and Animal Instincts (1992).

[3] G. Gordon Liddy Takes a Whipping by Karen Freifeld, Doug Vaughan & Linda Stasi, Newsday, 2nd May 1990.

This was also the last movie to be released by Manson International.

LikeLike